Alcohol consumption is deeply embedded in social and cultural practices worldwide. However, scientific understanding of alcohol’s health impact has evolved significantly over the past decade. Alcohol is now classified as a Group 1 carcinogen by the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer, placing it alongside tobacco smoke and asbestos.

What is increasingly clear from both research and clinical practice is that alcohol is not merely associated with cancer through indirect lifestyle factors. It directly contributes to carcinogenesis through biological mechanisms that damage DNA and impair DNA repair.

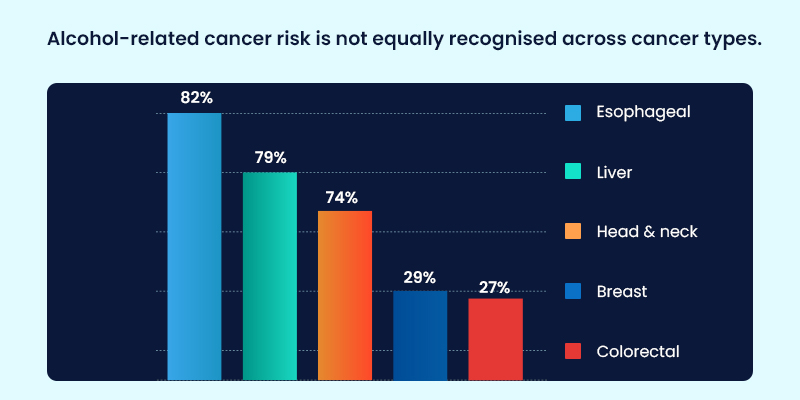

Yet, despite the strength of this evidence, alcohol-related cancer risk is not always reflected consistently in real-world clinical conversations, a gap that has meaningful implications for prevention and patient outcomes.

Does Alcohol Cause Cancer?

Large epidemiological and genetic studies now demonstrate that alcohol consumption contributes causally to multiple malignancies, even at low to moderate levels of intake. Cancers with strong causal links include:

- Oral cavity, pharyngeal, and laryngeal cancers

- Esophageal cancer

- Hepatocellular carcinoma

- Breast cancer

- Colorectal cancer

From a scientific standpoint, no level of alcohol consumption is completely risk-free. Risk increases progressively with cumulative exposure over time.

However, real-world oncology insights tell a more complex story.

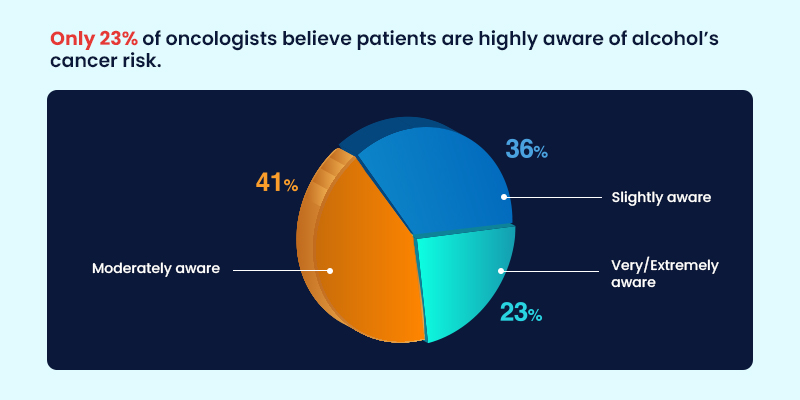

Data collected through MDForLives surveys of oncologists across multiple countries indicate that alcohol consumption is not consistently assessed as part of cancer risk evaluation or survivorship care. While the evidence base is strong, its translation into routine practice varies, highlighting a disconnect between what research confirms and what is regularly discussed with patients.

This gap matters, because risk awareness is a prerequisite for prevention.

Alcohol Consumption and Cancer Risk: Evidence Meets Practice

For years, researchers debated whether alcohol itself caused cancer or whether observed associations were driven by confounding factors such as smoking or diet. Advances in genetic epidemiology have resolved this question.

Large population-based studies led by Oxford Population Health and international collaborators demonstrate that alcohol independently increases cancer risk. Globally, alcohol consumption is estimated to have contributed to approximately 740,000 new cancer cases in 2020. These findings reinforce alcohol’s role as a direct carcinogen, strengthening global cancer prevention strategies and informing evidence-based public health messaging.

Yet oncologists report that patient awareness often lags behind the science.

According to real-world clinical perspectives captured through MDForLives, many patients continue to associate alcohol-related harm primarily with liver disease, rather than recognizing its role in a broader range of cancers. This limited awareness can weaken preventive counseling and delay meaningful behavior change.

Alcohol Intake, Genetics, and Clinical Reality

Genetic studies provide some of the strongest causal evidence linking alcohol to cancer risk. Variants affecting alcohol metabolism, particularly ALDH2 and ADH1B,lead to acetaldehyde accumulation, a known carcinogen that damages DNA and disrupts repair mechanisms.

From a research perspective, these findings are well established.

From a clinical perspective, MDForLives survey insights suggest that genetic susceptibility is not routinely discussed during alcohol-related cancer counseling. Time constraints, competing priorities, and uncertainty about how to communicate genetic factors in cancer risk, contribute to this gap.

This represents a missed opportunity to personalize risk discussions and reinforce the biological basis of alcohol-related carcinogenesis.

How Does Alcohol Cause Cancer?

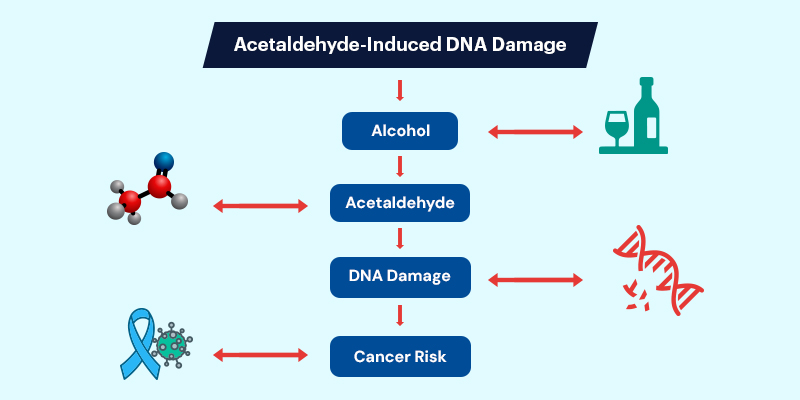

Acetaldehyde-Induced DNA Damage

Alcohol metabolism converts ethanol into acetaldehyde, a highly reactive compound capable of forming DNA interstrand crosslinks. These lesions disrupt replication and transcription, leading to mutations and chromosomal instability.

Impaired DNA Repair Mechanisms

Repair pathways such as the Fanconi anemia pathway are critical for correcting this damage. When these systems are overwhelmed either by excessive exposure or impaired detoxification, burden increases.

Research intoDNA damage and impaired repair mechanismsdemonstrates that individuals with compromised detoxification or repair pathways face a disproportionately higher cancer risk when exposed to alcohol.

Real-world oncology observations support these mechanisms.

Clinicians report observing differences in disease progression, recurrence, or treatment tolerance among patients who continue alcohol consumption after diagnosis, reinforcing what molecular biology predicts.

Alcohol and Synergistic Cancer Risks

Alcohol amplifies the effects of other carcinogens. In smokers, increased mucosal permeability enhances exposure to tobacco-derived toxins, significantly raising head and neck cancer risk. Alcohol also alters hormonal regulation, contributing to increased breast cancer risk even at relatively low intake levels.

Despite this, MDForLives insights indicate that low or moderate alcohol intake is not always perceived as clinically relevant, either by patients or consistently by clinicians underscoring the need for clearer, evidence-aligned messaging.

Does the Type of Alcohol Matter?

Research comparing beer, wine, and spirits has not identified a safer alcoholic beverage from a cancer risk perspective. Ethanol itself is the carcinogenic agent.

From a prevention standpoint, total alcohol exposure matters more than beverage type—a point that is often misunderstood in real-world patient discussions.

Does Quitting Alcohol Reduce Cancer Risk?

Yes. Cancer risk declines progressively after alcohol reduction or cessation. For cancers of the oral cavity, esophagus, and liver, measurable reductions in risk have been observed within years.

Real-world insights reinforce that patients who understand this benefit are more likely to consider behavior change, highlighting the importance of consistent, evidence-based counseling.

Ethical and Public Health Implications

Despite strong evidence, alcohol is still widely perceived as harmless or even beneficial in moderation. MDForLives real-world data suggests that this perception persists not only among patients, but also within fragmented clinical communication.

Closing the gap between evidence and everyday practice requires:

- Clear, non-stigmatizing messaging

- Consistent inclusion of alcohol risk in cancer care discussions

- Translation of molecular evidence into patient-understandable insights

Conclusion: Why Real-World Insight Matters

Alcohol is firmly established as a direct carcinogen that damages DNA and impairs repair mechanisms. Genetic and epidemiological studies confirm causality.

What real-world oncology insights add is context:

- Where conversations break down

- Where awareness is incomplete

- Where prevention opportunities are missed

By capturing perspectives from clinicians actively involved in cancer care, platforms like MDForLives transform scientific evidence into actionable, practice-informed insight, bridging the gap between what we know and what patients experience.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cancer caused by alcohol?

Alcohol is most strongly linked to cancers of the mouth, throat, esophagus, liver, breast, and colorectal region.

Which organs are most affected by alcohol consumption?

Alcohol most commonly damages the liver, brain, heart, and pancreas due to their roles in metabolism and inflammation.

How much alcohol increases cancer risk?

Even low levels of alcohol intake — such as one drink per day — have been associated with increased cancer risk, particularly for breast and upper digestive tract cancers.

Does quitting alcohol reduce cancer risk?

Yes. Cancer risk decreases over time after alcohol cessation, with greater reductions observed the longer abstinence is maintained.

Do genes influence alcohol-related cancer risk?

Yes. Genetic variants affecting alcohol metabolism, such as ALDH2 and ADH1B, significantly modify cancer risk by influencing acetaldehyde exposure.

MDForLives is a global healthcare intelligence platform where real-world perspectives are transformed into validated insights. We bring together diverse healthcare experiences to discover, share, and shape the future of healthcare through data-backed understanding.