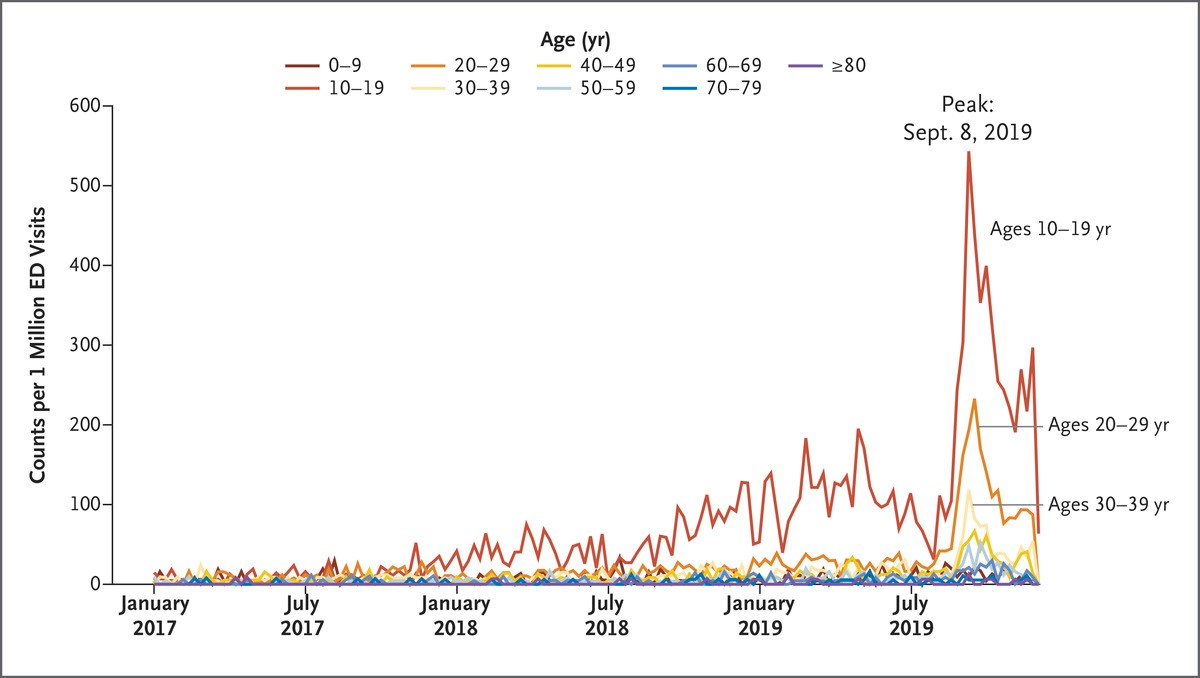

A recent report by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in the US raised concerns regarding the use of E-cigarettes and their association with Acute Pulmonary Injury (API) related to Emergency Department visits. In this report, data obtained from the National Syndromic Surveillance Program (NSSP) indicated an “outbreak” of Acute Pulmonary Injury (API) related ED visits in September of 2019. Interestingly, most of the patients presenting to EDs were aged 10-19 years old. It is also reported that the number of ED visits has markedly declined in October and November of 2019, but has not returned to pre-outbreak values.

Beyond the fact that the outbreak involved adolescents and young adults, another interesting finding was that 80% of patients were using Tetra-Hydro-Cannabinol (THC) products. At the same time, 35% were exclusively using THC containing products. On the other hand, 13% were exclusively using nicotine products. This finding is highly suggestive that THC containing products are the culprit behind this outbreak. Furthermore, bronchoalveolar fluid lavage samples identified vitamin E in 48 of the 51 samples tested, while it was not traced in the samples of the 99 healthy controls. This could indicate vitamin E as the causative agent, but the available data is far from providing conclusive evidence in that matter.

The CDC has subsequently issued interim guidance for healthcare professionals evaluating and caring for patients with suspected E-cigarette or vaping product use associated lung injury in December of 2019. They have also provided an updated algorithm for the management of patients with such symptoms as well as a discharge readiness list

Since their first appearance in the market in 2003, electronic cigarettes have been gaining increasing popularity, with global sales of around $7 billion in 2014. What is of particular concern is that as much as 13% of high school students in the US reported using an electronic cigarette at least once in the previous month.

Today, the use of E-cigarettes remains controversial. The scientific community has had mixed feelings regarding their use, both as a smoking cessation aid as well as recreationally. E-cigarettes seem to be less harmful than tobacco. This was demonstrated in a report by Public Health England in 2015, which concluded that E-cigarettes were 95% less harmful than tobacco. However, there are several potential risks that have to be addressed. In terms of smoking cessation, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 20 relevant trials reported that E-cigarette users were 28% less likely to quit smoking than those who did not use E-cigarettes. Overall, the currently available data do not provide sufficient evidence for the utilization of E-cigarettes in smoking cessation programs.

One of the main arguments of those who oppose the use of E-cigarettes is based on the “Gateway Theory”. This refers to E-cigarettes opening up a gateway towards the use of much more illicit as well as toxic drugs through vaping devices. The recent outbreak reported by the CDC could very well be a manifestation of such an event. Physicians around the world should be aware of this particular situation as well as keep up to date with the signs and symptoms as well as the management of patients presenting to the ED with Acute Pulmonary Injury (API) related to the use of THC containing vaping products.

Also read

4 Comments

World Blood Donor Day 2020 - Give Blood, Give Life - MDforLives

5 years ago[…] belief is that cigarette smokers and alcoholic beverage drinkers are not permitted to donate. This, however, is also false, but it […]

Respiratory Care Week | October 20 - 26, 2020 | MDforLives

5 years ago[…] smoke. Cigarette smoking is one of the major causes of lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Primarily, smoking causes initial inflammation of the airways and eventual destruction of […]

GIVE BLOOD, GIVE LIFE: World Blood Donor Day 2020 - MDForLives

4 years ago[…] belief is that cigarette smokers and alcoholic beverage drinkers are not permitted to donate. This, however, is also false, but it […]

Respiratory Care Week | October 2020 - MDForLives

4 years ago[…] smoke. Cigarette smoking is one of the major causes of lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Primarily, smoking causes initial inflammation of the airways and eventual destruction of […]