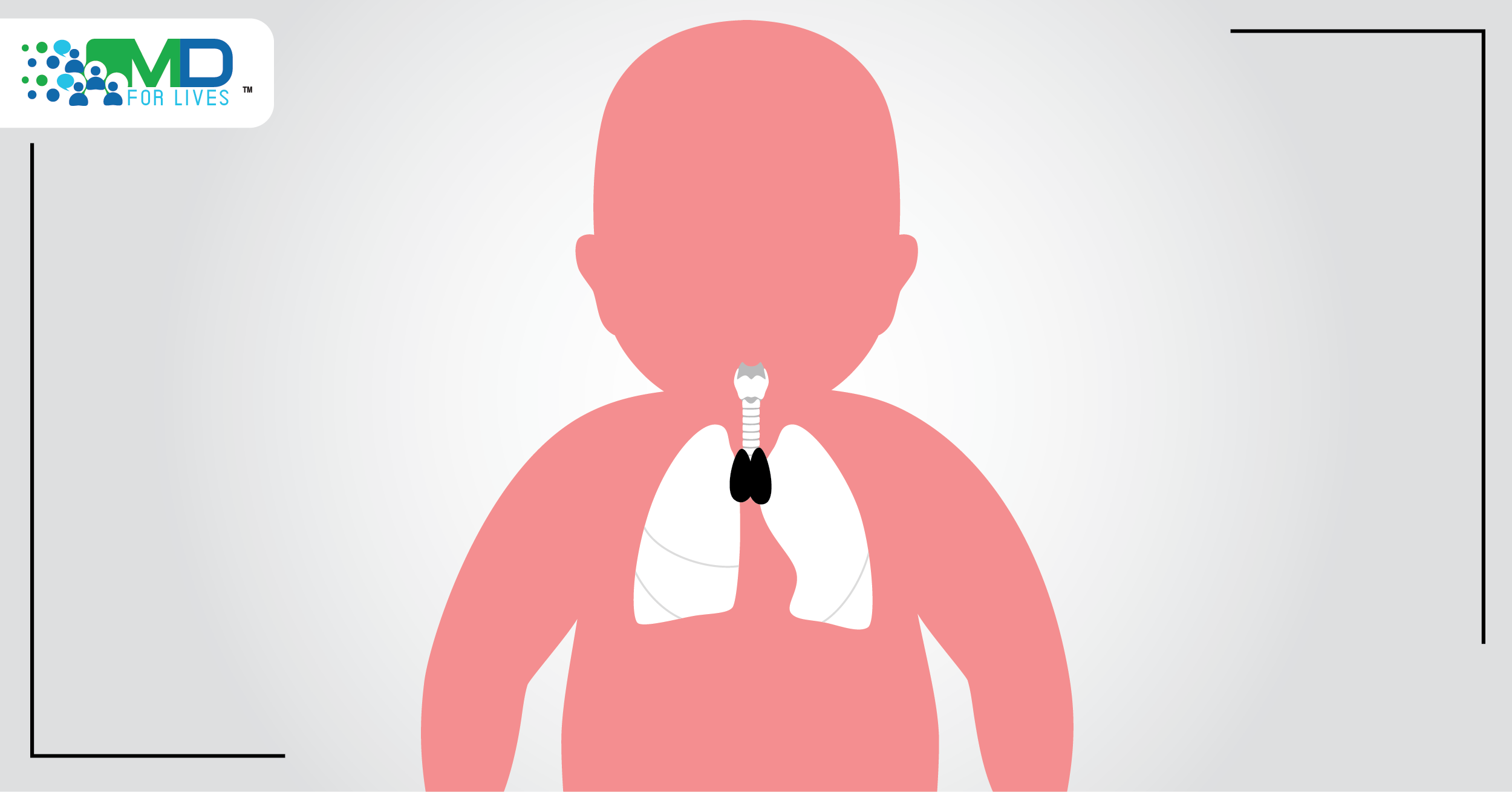

Congenital athymia is a rare condition in which babies are born without a thymus. As a result, the immune system is severely impaired, and children historically die from infections before the age of two. Now, the FDA has approved a tissue culture-derived product that represents the first treatment for this devastating disorder.1

What is congenital athymia?

A functioning thymus gland is essential to the development of the immune system in babies and children. The thymus stimulates lymphocytes to mature into various types of T cells, and it is the site of negative T cell selection, in which T cells that target the individual’s own cells are weeded out to prevent autoimmunity.2,3

Babies born without a thymus gland have profound immunodeficiency with the absence of immunocompetent T cells, leading to frequent and severe infections beginning soon after birth. Another major potential consequence is autologous graft versus host disease (GVHD), in which T cells attack the patient’s own organs. This occurs due to the lack of T cell selection and proper development in the thymus.2

Possible cases of congenital athymia can be picked up on newborn screening available throughout the US, and the diagnosis can be confirmed using flow cytometry and genetic studies.2 It is important to distinguish congenital athymia from severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) so that appropriate treatment can be offered.

The most common cause of congenital athymia is complete DiGeorge syndrome. This syndrome, caused by the deletion of a portion of chromosome 22, also leads to heart defects and abnormalities in other body systems. While individuals with milder forms of DiGeorge syndrome may have a small thymus and some immune impairment, complete DiGeorge syndrome involves the total absence of the thymus.2,4 Other genetic causes of congenital athymia include CHARGE syndrome, CHD7 mutation, and FOXN1 deficiency.2,4

Environmental exposures in the womb – including exposure to retinoic acid and to the effects of maternal diabetes mellitus – are also thought to rarely lead to congenital athymia, but more research is needed.2

Previously available treatments

To reduce the risk of serious infections, patients are typically placed in isolation and given immunoglobulin replacement and antimicrobial prophylaxis. Steroids or calcineurin inhibitors are used to prevent autoimmune damage in patients who are at risk for GVHD. These supportive treatments cannot prevent all infections and typically do not extend life beyond early childhood.5 Hematopoietic stem cell transplant has been attempted but has shown poor success rates in congenital athymia patients.2

Human thymus gland cross-section under a microscope. The FDA has approved a technique for harvesting and culturing a donor thymus tissue and implanting it into babies and children born without a thymus.1

New treatment

For decades, doctors and scientists have been working on a technique for harvesting and culturing the donor thymus tissue and implanting it into babies and children born without a thymus. Now, the FDA has approved the treatment, dubbed Rethymic, after results from the trial showed that most of the treated children survived long term.1,5

Because congenital athymia is so rare, the clinical trials for Rethymic spanned from 1993 to 2020 and involved 105 children. The 95 treated patients included in the primary efficacy analysis spanned from 33 days to 3 years of age and included patients with complete DiGeorge syndrome, CHARGE syndrome, CHD7 mutation, FOXN1 deficiency, and other etiologies. Among these children, the Kaplan Meier estimated survival rate was 77% (95% CI, 0.670, 0.841) at 1 year post-treatment. Ninety-four percent of the patients who survived to 1 year were still alive at the last follow-up (median 10.7 years).5

Adverse events associated with the treatment included hypertension, cytokine release syndrome, rash, renal impairment, and others.5

The treatment is manufactured by Enzyvant specifically for each patient. Immune reconstitution occurs over the course of 6 to 12+ months after the tissue is surgically implanted; patients and caregivers must continue to follow strict infection control procedures and prophylactic medications should be continued during this time.1,5