In Plato’s book, The Theaetetus, Socrates was at wrestling school, discussing what he believed ‘knowledge’ to be to his friend Theaetetus, “Nothing is in itself just one thing…Everything is in a process of coming to be”,

“For, what is knowledge?”, he continued, “Knowledge is form, geometry, astronomy, harmony, arithmetic.”

Theaetetus disagreed, believing knowledge had a more dream-like form, made of “perception, true belief and logos“.

The pair at loggerheads, Socrates parted ways by suggesting, “maybe knowledge is being able to tell some mark by which the object you are asked about differs from all other things”. He then walked off to court to face a criminal indictment.

Philosophers have often played on the dichotomy of the end being the beginning. This intangible thing that, as Aristotle put it, “begins in wonder and ends with death”. It is a sentiment many doctors cite when discussing cancer and the medicines we use to treat it.

When it comes to clinical trial data, the endpoint is a word every physician hears, but few fully agree on. Remarkable new immunotherapies, targeted therapies, biomarker discoveries, and revolutions in radiation and chemotherapy are coming to the fore, how then to sort the chaff from the wheat? Choice befuddles the senses – A truism that dogs the multidisciplinary team (MDT), the value analysis committee (VAC), the clinical commission group (CCG) all the way to the national and international regulatory bodies (FDA, EMEA, NICE, etc,).

The problem is, there is too much quantity and too little quality. Trials that cost billions and end in limbo. Trials that reach phase 4, even phase 5 and still cannot cut the mustard. Still, we must persevere, for everything is in the process of coming to be.

It has never been as important, therefore, for pharmaceuticals to assist the physician in determining what valuable endpoints they use when trialing their novel therapies. As an oncologist, I can only speak for what I like. I want differences. I want a drug to stand out from its competitors, from its comparator arms. I want clinically meaningful progress from the standard of care.

The issue arises with the quality of clinical data. The assessment teams, (locally, regionally, nationally, internationally) not only have to assess inclusion criteria, comorbidities, age, risk scores, previous treatments, ethnicity, gender, but also conflicting factors like missing data and infrequent assessments which can complicate the evaluation of symptom data, particularly for time-to-deterioration analyses.

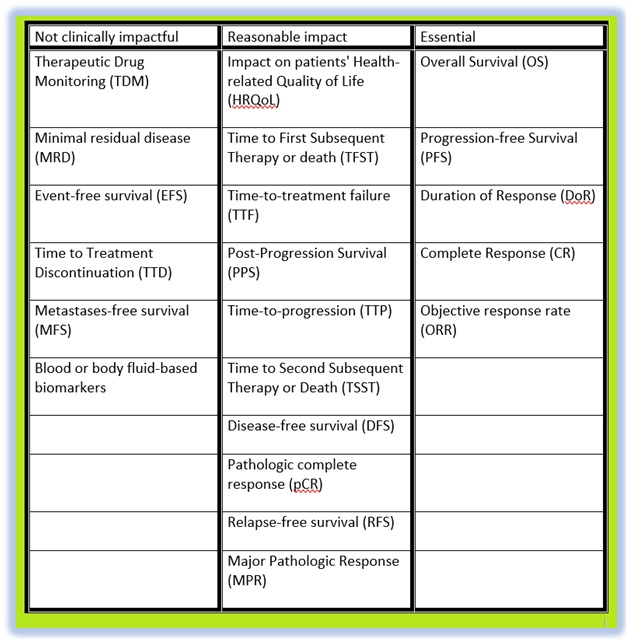

I have listed into a 3 part table, information that I find valuable when considering the efficacy of new cancer treatment:

The above list is endpoints that have been used throughout clinical trials over the last 30 years. Some of these are ranked in the upper echelons of meaningful trial data:

- Overall Survival (OS) is the gold standard, the yardstick that hopefully tells us how long this patient will live on this treatment? It is generally reported of up to 5 years of evidence, though the more years OS data the better.

- Progression-free Survival (PFS) is the most prominently used throughout clinical trials. It shows us survival without the progression of the disease. If a trial does not deliver this information, then it brings into doubt a drug’s efficacy.

- Complete response (CR) – Though it does not necessarily mean the patient is cured, it is the best result that can be reported, meaning the cancerous tumor is now gone and there is no evidence of disease.

- Duration of Response (DoR) is the most widely cited amongst the physicians in my establishment, due to its ability in telling us this drug can produce a durable, meaningful delay in disease progression, compared to a temporary response without any lasting benefit.

The other endpoints in the table are either considered not as impactful, at least in our hospital’s decision-making process, or repeatable terms that confuse the matter.

The blood or body fluid-based biomarker endpoint is useful in offering us data on significant decreases in performance status, bowel obstruction, marked increases in CA-125 (in the case of progression for ovarian cancer), paraprotein levels measured in blood and urine (for myeloma response criteria), durable major molecular response (in chronic myelogenous leukemia). However, they are seen as too specific and harder to compare within a general patient population. In the future, they will no doubt come to the fore, as we isolate enough subsets of conditions.

In the case of Minimal Residual Disease (MRD), which has been used as a surrogate endpoint for accelerated approval of acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and Metastasis-free Survival (MFS), which has been used as a clinical endpoint for non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, both were adopted without consultation to any regulatory body, probably as a means to fast-track drugs. All this subterfuge makes it harder to assess how to utilize the data in the best way, as we have to compare it to existing terminology. Consistency is needed, though the door is open to new criteria. A pharmaceutical company trialing their new drug should try their best to not ‘fix data’ (i.e., give us weaker endpoints to highlight a drug’s efficacy, in order to push a drug quicker through the process), as it only succeeds in sending us warning signs, another attempt to make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear.

The following are a list of criteria more likely to be accepted as an alternative to an OS (Overall Survival) endpoint in validating drug efficacy and its use for my patients:

- Where the drug demonstrates significant improvement in safety and tolerability.

- Where baseline patient survival < 2 years.

- For early line (e.g., 1st line) metastatic cancer.

- For early-stage (non-metastatic) cancer.

- Where the drug demonstrates significant improvement in health-related quality of life.

- For orphan indications.

- Where baseline patient survival > 2 years.

- For cancers with high unmet need.

- For a localized disease with the drug used in an adjuvant setting.

- For localized disease with the drug used in the neo-adjuvant setting.

When it comes to the adoption of new technologies, or new data sources (e.g., smartphone apps), in addressing measurability of endpoints such as Patient Reported Outcomes (PRO) and Quality of Life (QoL), I would assess each point using the following 3 factors:

- Are they excellent sources to collect patient data and should be leveraged more often?

- Are they interesting sources of information, though have limitations thus should be used on a case-by-case basis?

- Do they have significant limitations which are difficult to overcome and should therefore never be used to collect patient data?

Overall, what I believe constitutes a “good” endpoint is:

- Clinical relevance and interpretability (e.g., strongly associated with health outcomes).

- Reproducibility and objectively measured without any subjective interpretation (e.g., to ease monitoring of a unique patient in time or make comparisons between patients).

- Easily measured, without additional risk, at low cost, at minimal inconvenience for the patient.

- Validity and robustness (i.e., correlation with patient health status without interdependence to other interventions).

In the end, a clinical trial is a method that eventually gets to the right point, be it the right dosage of chemo or radiotherapy, the right choice of immunotherapy or targeted therapy, the right biomarker, etc. The physician should support the pharmaceutical company as much as the pharma supports the physician. We put so many roadblocks into allowing new medicines to pass through, some of them necessary, some of them time-wasting bureaucracy. But if we have any hope of harmony, we need to keep trialing, and failing and learning. That is knowledge.

As Socrates remarked to Theaetetus, “Discover what you don’t know, so you may be able to approach the topic better in the future“.