The rates of hypertension among pregnant women have been creeping up for decades. Today, over 8% of pregnant women in the US have hypertension at some point in their pregnancies, and over 2% begin their pregnancy while already experiencing chronic hypertension.

On May 12, 2022, in the New England Journal of Medicine, a research group reported on a clinical trial on the impacts of treatment with hypertension medication during pregnancy. They found that pregnancy outcomes were better among women randomized to be treated with the medication compared to those who were not given medication unless their hypertension became severe, without a significant increase in fetal or neonatal complications.

Hypertension in Pregnant Women

Pregnant women with high blood pressure often experience few or no hypertension symptoms, but this does not mean the condition is harmless. Chronic hypertension during pregnancy increases the risk for preterm birth, low birth weight, placental abruption, preeclampsia, and death of the fetus or newborn.

The rising rates of overweight, obesity, and births to women over 35 years of age are the factors driving increased hypertension in pregnancy in the US.2 Pregnancy itself can also cause hypertension: gestational hypertension refers to high blood pressure that develops after the 20th week of pregnancy. Chronic hypertension indicates high blood pressure that existed before their pregnancy or began before week 20.

In preeclampsia (a dangerous increase in blood pressure that can occur after week 20 of pregnancy or after giving birth), hypertension symptoms can include a persistent headache, swelling in the feet and hands, abdominal pain, changes in vision, and trouble breathing.

Guidelines recommend antihypertensive treatment for pregnant women with severe hypertension and those with kidney disease or other conditions that raise the risk of complications. For women with milder elevation in blood pressure (between 140/90 and 160/110 mm Hg), the evidence for and against hypertension treatment has not been clear-cut.

One concern has been that excessively lowering blood pressure using medications could potentially reduce blood flow to the placenta and cause fetal harm, growth restriction, or even death. For this reason, different medical societies have come to different conclusions on the issue of when to treat.

A trial explores treatment for Hypertension in Pregnancy

The Chronic Hypertension and Pregnancy (CHAP) Trial was conducted at over 70 locations in the US. This open-label, randomized trial recruited women at less than 23 weeks of pregnancy who had mild chronic hypertension (either new or preexisting).

The investigators screened 29,772 women and enrolled 2419 women in the trial; many of those who underwent screening were excluded because they had passed 23 weeks’ gestation or because their current blood pressures were below the threshold for the trial. The analysis included 1208 women randomly assigned to the active treatment group and 1200 women randomly assigned to the control group.

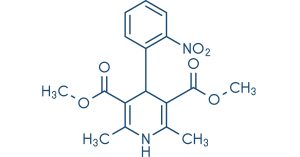

Women in the active treatment group were assigned to receive an antihypertensive (either labetalol or nifedipine) with a goal of maintaining blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg. Women in the control group did not receive medication; however, if they developed severe hypertension, with systolic pressure at or above 160 mm Hg or diastolic pressure at or above 105 mm Hg, they then began treatment with antihypertensives.

During the study period and before delivery, on average, the active treatment group maintained a blood pressure of 129.5 (systolic) over 79.1 mm Hg (diastolic) compared to 132.6 over 81.5 mm Hg for the control group.

Results from the CHAP trial

The trial’s active treatment group did significantly better when considering the primary outcome, which was a composite including preeclampsia with severe features, medically indicated preterm delivery before 35 weeks of pregnancy, placental abruption, or death of the fetus or newborn. At least one of these primary outcome events occurred for 30.2% of active-treated women and 37.0% of women in the control group (risk ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.73 to 0.92; P<0.001).

Meanwhile, the early treatment did not significantly increase the risk of lower birth weight for the newborns in the trial: 11.2% of actively treated and 10.4% of the control group women had infants born at weights below the 10th percentile for their gestational age (risk ratio, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.85 to 1.36; P=0.56). The risk of having a newborn with a weight under the 5th percentile and of having a newborn with a weight under 2500 g was also not significantly increased.

These results add to the ongoing discussion regarding how to treat mild hypertension among pregnant women. The trial’s findings will need to be confirmed, but they add support to the idea that pregnant women with mild hypertension can benefit from continuing or beginning antihypertensive treatment to attain a target blood pressure of 140/90 mg Hg.

References:

- https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2771113

- https://medlineplus.gov/highbloodpressureinpregnancy.html

MDForLives is a global healthcare intelligence platform where real-world perspectives are transformed into validated insights. We bring together diverse healthcare experiences to discover, share, and shape the future of healthcare through data-backed understanding.