When a patient presents with renal masses, how do you decide their candidacy for nephron sparing surgery?

The first recorded nephrectomy (Nx) was performed in 1861 by Erastus Bradley Wolcott in Wisconsin. The patient had been suffering from a large tumor and the operation was initially successful, but the patient died fifteen days later.

As techniques and technology have got better, radical nephrectomy had become standard of care as first line treatment of renal tumors.

Radical nephrectomy involves removing the entire kidney, along with a section of the tube leading to the bladder (ureter), the gland that sits atop the kidney (adrenal gland), and the fatty tissue surrounding the kidney. When both kidneys are removed at the same time, the procedure is called bilateral nephrectomy.

Partial nephrectomy (offering the benefit of sparing the kidney and saving kidney function) was only to be used if absolutely necessary (if the renal tumor is less than 7-cm or the patient has only one kidney). The guidelines for this pathway have changed over the course of time, and from today (2022) elective partial Nx is recommended for most T1a, T1b and some T2 tumors, as an optimal minimally invasive surgery.

What has brought about this change?

The answer is the technology and technique has vastly improved, as has surgical planning and training.

There has been a progression of more advanced and versatile robot variants:

There is also an improvement in more effective ultrasound techniques. With more versatile drop-in ultrasound probes, higher resolution images and robot integration.

There has been an improvement in Air-seal devices, with better valve-free access to abdominal cavity; intact specimen removal; unimpeded introduction and removal of clips, needles, sutures and mesh; better control over insufflation pressure; and venous clamping capability.

Overall, there has been a simplification in techniques. There are no longer any bolsters, rarely any hemostatic agents, no physical venous clamping, fewer sutures. We have contoured enucleation, rather than ‘pie-slice’ or polar resection. There is early unclamping, and selective clamping using green fluorescence. There is also widespread utilization of both transperitoneal and retroperitoneal access.

With all this technology and techniques at our fingertips, what are our responsibilities oncologically in these patients and how do we make these decisions in a rational fashion?

Case Study:

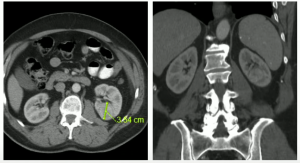

A 70-year-old man with well controlled hypertension, hyperlipidemia, normal renal function, discovered a 3.5mm endophytic left renal mass.

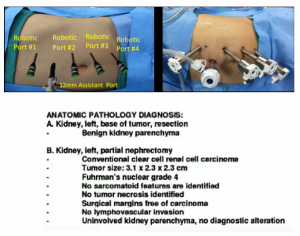

In July 2012, we performed an uneventful partial nephrectomy with robotic assistance.

Patient ended up pT1a staging. With post-operative serum creatinine of 0.9. Which was a good response to treatment.

We monitored the patient bi-annually until August 2019, when we lost him to follow up.

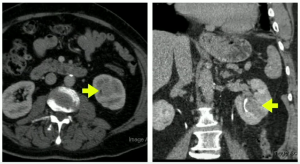

Then in 2021, the patient re-engages with us, at 79-years-old, with an ultrasound and CT scan, where we note a 3.5x5cm lesion in the left lower pole.

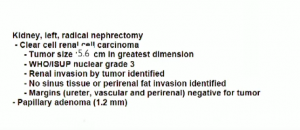

We did a salvage radical nephrectomy, results below:

Patient was pT3a (renal vein invasion), with Post op serum Cr.1.6

Patient is doing well and has not developed metastasis (Mar 2022).

The question is, did we do the right thing here?

How should postoperative oncologic factors drive our decisions concerning suitability for nephron sparing surgery?

Nephron sparing is seen to be better for holistic patient outcomes, more than nephron wasting approaches. Nephron sparing has a higher risk of complications, but this risk is usually outweighed by the benefit of renal preservation.

Decision making about suitability is not solely an oncologic decision. Resecting more complex tumors may be associated with higher perioperative complication risks (bleeding, angiographic embolization, urine leaks). Resecting more complex tumors is likely to result in more renal functional loss. Older or sicker patients are less able to tolerate lengthy surgery, so many not be good candidates. Older patients also are less likely to gain from nephron sparing due to life expectancy.

What is the risk of pathologic upstaging of “Resectable appearing” tumors? Is there a difference between renal sinus and perinephric fat involvement of pT3 tumors?

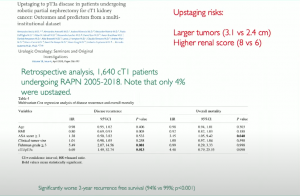

Data from a trial in 2020, showed a small but worse response in T3 disease patients that were upstaged

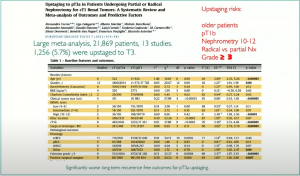

And a study from 2021, using 22,000 patients form 13 studies, showed 5.7% of patients upstaging to T3 disease.

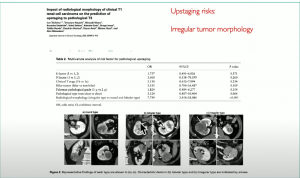

Another study from 2021, showed there is more likelihood of upstaging with irregular shaped tumors:

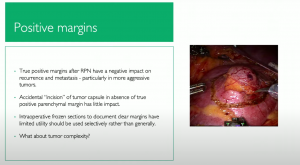

Also, how does tumor complexity impact on positive margins and how do these alter outcome?

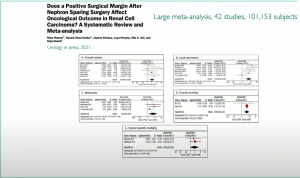

In a study in 2021, on if a positive surgical margin (PSM) after nephron sparing surgery affect oncological outcomes, they showed PSM adversely affects oncologic outcomes and is directly associated with an increased risk of recurrence and mortality.

And what is the risk of de-novo ipsilateral second primary tumors in the future and does pathology and stage alter this risk in some fashion?

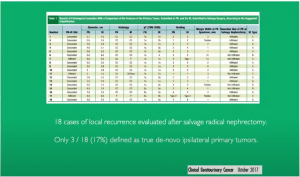

A study in 2017 only marginal risk factors (3/18) defined as ipsilateral primary:

Multifocality in Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC) outside of established genetic syndromes is patient centric rather than tumor centric.

There is potential for true multifocality, but this likely has more to do with underlying genetic risk factors than it does with the characteristics of the original primary tumor. There is tremendous inter and intra tumor heterogeneity in RCC. But given our current lack of deep insight into the genetic background of human RCC tumors preoperatively, it is unlikely that the risk of second ipsilateral primary tumors should drive nephron-sparing decisions in sporadic cases. Keep in mid that the underlying genetic background is shared between both kidneys.

Upstaging of cT1 tumors to pT3a tumors at partial nephrectomy is relatively rare (<5%) and portends a statistically significant if rather modest negative impact on recurrence free survival. The risk of upstaging appears to be higher for large tumors, higher RENAL scores, higher grade tumors and those with irregular morphology. Renal sinus fat invasion does not appear to be higher risk for poor oncologic outcomes than perinephric fat invasion. There is also little data supporting better oncologic outcomes for radical nephrectomy as compared to partial Nx for completely resected pT3 RCC.

It seems true positive surgical margins after partial nephrectomy have a very significant impact on oncologic outcomes. Larger tumors with higher RENAL scores raise the risk of positive margins at PN. Given the oncologic effect of positive margins, particularly in higher aggressive tumors, we should consider salvage nephrectomy.

MDForLives is a global healthcare intelligence platform where real-world perspectives are transformed into validated insights. We bring together diverse healthcare experiences to discover, share, and shape the future of healthcare through data-backed understanding.