Across oncology practice, treatment decisions are increasingly shaped by molecular stratification rather than tumor location alone.Targeted therapy for cancer has reshaped modern oncology by moving treatment away from broad, non-specific chemotherapy toward precision-based approaches that act on defined molecular targets within cancer cells. Unlike traditional chemotherapy, which can damage both cancerous and healthy tissues, targeted cancer therapy focuses on specific genetic mutations, receptors, or signaling pathways that drive tumor growth and survival. As a result, targeted therapy for cancer treatment is increasingly guided by molecular profiling to ensure the right therapy reaches the right patient at the right time. With advances in molecular diagnostics and biomarker testing accelerating, targeted therapy is becoming part of standard cancer care worldwide.

What is Targeted Therapy?

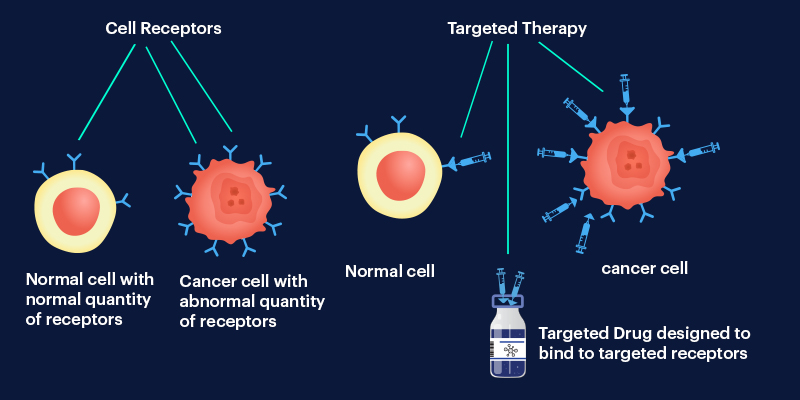

Targeted therapy for cancer uses drugs or other substances to identify and attack cancer cells based on molecular features unique to the tumor. These therapies act on defined targets such as mutated genes, overexpressed receptors, or dysregulated intracellular signaling pathways essential for tumor proliferation and survival.

By focusing on cancer-specific mechanisms, targeted therapies aim to limit collateral damage to normal tissues, resulting in a more favorable safety profile compared with chemotherapy. In real-world care, the effectiveness of targeted therapy depends as much on patient selection as on the drug itself.

What are the Types of Targeted Therapy?

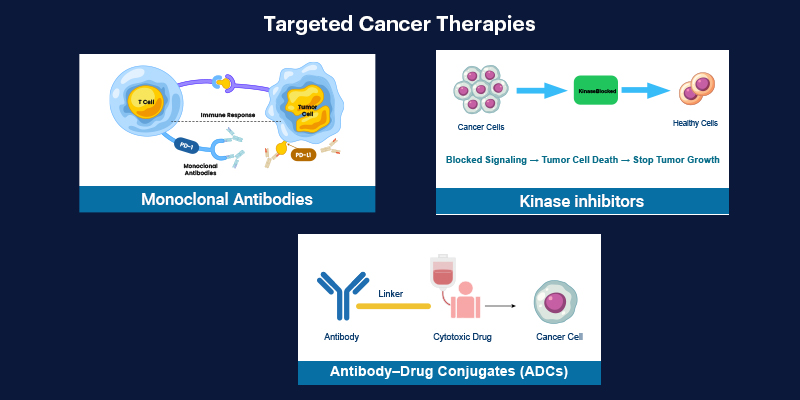

Targeted therapies can be broadly categorized based on their mechanism of action:

- Monoclonal antibodies that bind extracellular targets such as HER2, EGFR, or VEGF

- Small-molecule inhibitors that block intracellular kinases and signaling cascades

- Angiogenesis inhibitors that disrupt tumor blood supply

- Hormone-related targeted therapies used in hormone-driven malignancies

- Antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) that deliver cytotoxic agents directly to cancer cells

Among these, kinase inhibitors and antibody–drug conjugates are currently seeing the fastest clinical adoption, reflecting both expanding molecular targets and improved delivery strategies.

Who is Eligible for Targeted Therapy in Cancer?

Targeted therapy is recommended for patients whose tumors express actionable molecular markers identified through genomic or biomarker testing. Eligibility depends on cancer type, disease progression, prior treatments, and molecular profile. As actionable targets expand beyond single mutations, eligibility assessment increasingly requires multidisciplinary clinical judgment rather than algorithmic decision-making alone.

Targeted Therapy Administration

Targeted therapies may be administered orally, intravenously, or subcutaneously. Treatment duration and dosing schedules vary depending on drug pharmacokinetics, toxicity profile, and therapeutic intent, such as induction, consolidation, or maintenance therapy.

Examples of Targeted Therapies

Widely used targeted agents include:

- Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

- Monoclonal antibodies

- PARP inhibitors

- CDK4/6 inhibitors

- Combination targeted regimens under clinical evaluation

Many of these agents are now being studied in combination regimens to improve durability of response and overcome resistance mechanisms.

What Kind of Cancer Does Targeted Therapy Treat?

Targeted cancer therapy is used across a wide range of malignancies, including breast cancer, lung cancer, colorectal cancer, leukemias, lymphomas, melanoma, ovarian cancer, prostate cancer, and select sarcomas.

In non–small cell lung cancer, molecularly guided treatment has become essential following progress in KRAS targeted therapy, offering new options for patients with historically poor prognoses.

How Does Targeted Therapy Work Against Cancer?

Targeted therapy works by disrupting biological processes that cancer cells rely on for survival and proliferation. These include blocking growth signals, inhibiting angiogenesis, triggering apoptosis, and interfering with immune evasion pathways.

Increasingly, targeted therapies are evaluated alongside immune-based treatments. Research into breakthroughs in immunotherapy and early cancer detection supports a combined approach that enhances treatment efficacy and long-term disease control.

What Happens During a Targeted Therapy Procedure?

Before initiating targeted therapy, patients typically undergo molecular profiling, imaging studies, and baseline laboratory evaluations. These steps are increasingly important for treatment planning, patient counselling, and shared decision-making in precision oncology.

Cancer Targeted Therapy Clinical Trials

While clinical trials establish efficacy, real-world clinician experience increasingly shapes how targeted therapies perform across diverse patient populations. Platforms such as MDForLives help capture clinician and patient insights that complement clinical trial evidence, informing oncology research beyond controlled study settings.

Clinical trials remain central to advancing targeted cancer therapy. Recent studies focus on next-generation kinase inhibitors, antibody–drug conjugates, and rational combination regimens designed to delay resistance.

What are the Side Effects of Targeted Therapy?

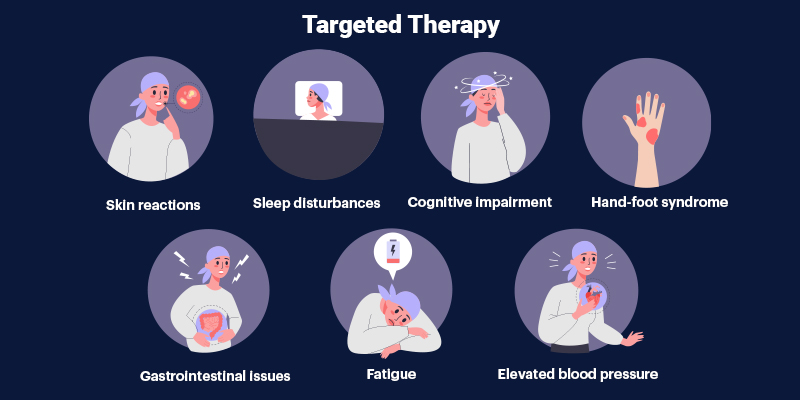

Although targeted therapies are generally better tolerated than chemotherapy, adverse effects can still occur. Common side effects include dermatologic reactions, fatigue, hypertension, gastrointestinal symptoms, and organ-specific toxicities depending on the drug class. Continuous monitoring and early management remain essential.

What is the Role of Targeted Therapy in Cancer Treatment?

Targeted therapy has become a cornerstone of precision oncology, enabling clinicians to personalize treatment based on tumor biology rather than anatomical sites alone.

In cancers such as cervical cancer, where prevention, early detection, and molecular stratification influence outcomes, targeted approaches complement established protocols, as seen in evolving cervical cancer treatment strategies.

Conclusion

Targeted therapy for cancer represents a major advancement in modern oncology, offering treatments that are biologically precise and increasingly effective. As oncology continues to integrate molecular science with real-world evidence, the future of targeted therapy will be defined not just by innovation, but by the quality of insight connecting research to clinical practice.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Can You Expect When Having Targeted Therapy?

Most patients experience fewer systemic side effects than with chemotherapy, though regular monitoring is required.

What’s the Success Rate for Targeted Therapy?

Success varies by cancer type, biomarker status, and disease stage, with many therapies showing significant improvements in progression-free survival.

When Is Targeted Therapy Recommended?

When molecular testing identifies actionable targets and clinical evidence supports benefit.

Can Targeted Therapy Cure Cancer?

While not universally curative, targeted therapy can lead to long-term remissions in selected cancers.

What are Targeted Cancer Drugs?

They are drugs designed to interfere with specific molecular targets involved in cancer growth.

How is Targeted Therapy Different from Chemotherapy?

Chemotherapy is broadly cytotoxic, whereas targeted therapy acts on defined molecular pathways with greater specificity.

MDForLives is a global healthcare intelligence platform where real-world perspectives are transformed into validated insights. We bring together diverse healthcare experiences to discover, share, and shape the future of healthcare through data-backed understanding.