CRISPR gene editing has evolved from a naturally occurring bacterial immune mechanism into one of the most influential technologies in modern medicine, building decades of progress in gene therapy. Since its adaptation as a programmable gene‑editing tool in 2012, CRISPR gene editing has enabled researchers and clinicians to introduce highly targeted changes to DNA with unprecedented precision. Today, it underpins approved therapies, advanced diagnostics, and translational research that reshape how genetic diseases are understood and treated, including the emerging clinical use of CRISPR gene editing across multiple specialties

What is CRISPR?

CRISPR—Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats—originated as an adaptive immune system in bacteria. By capturing fragments of viral DNA, bacteria retain a molecular memory that allows rapid recognition and destruction of future infections. Scientists repurposed this system by combining a programmable guide RNA with CRISPR‑associated enzymes such as Cas9, transforming CRISPR into a precise and scalable gene editing technology applicable across biological systems.

How CRISPR Gene Editing Works?

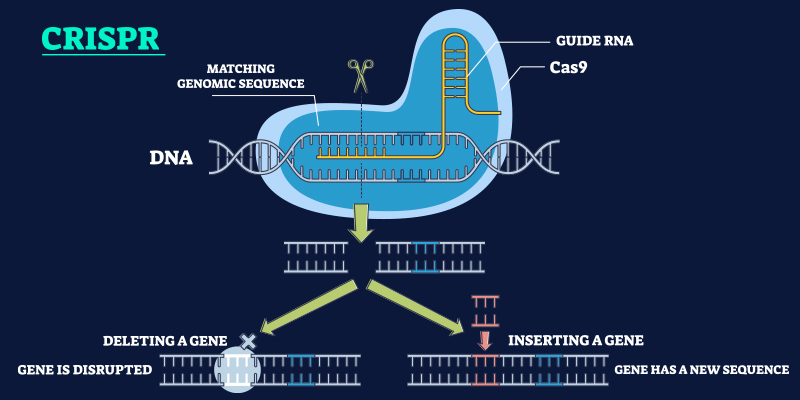

CRISPR gene editing functions through a targeted, sequence‑specific mechanism:

- A guide RNA (gRNA) is engineered to match a specific DNA sequence.

- The Cas9 enzyme is directed to this genomic location and introduces a precise cut.

- The cell’s intrinsic DNA repair machinery then repairs the break, either disrupting a faulty gene or incorporating corrected genetic information.

More recent advances, including base editing and prime editing, enable single‑nucleotide modifications or search‑and‑replace edits without inducing double‑strand breaks. These next‑generation approaches significantly improve precision and reduce off‑target effects, increasing the clinical safety profile of CRISPR gene editing.

Research Origins and Scientific Progress

The scientific origins of CRISPR gene editing trace back to early 2000s microbiology research focused on understanding how bacteria survive repeated viral infections. Researchers observed unusual, repetitive DNA sequences in bacterial genomes that appeared to store fragments of viral genetic material. These sequences—later termed CRISPR—functioned as a form of adaptive immune memory, allowing bacteria to recognize and neutralize previously encountered viruses.

A breakthrough came when scientists identified CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins, particularly Cas9, as the molecular machinery responsible for cutting viral DNA. Building on foundational work from European research groups, Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier demonstrated in 2012 that the CRISPR–Cas9 system could be reprogrammed with a synthetic guide RNA to introduce precise, targeted breaks in DNA. This discovery established CRISPR as a versatile and accessible genome-editing platform.

Following this landmark finding, research rapidly expanded across model organisms, including plants, mice, and non-human primates. By 2014, proof-of-concept studies demonstrated that CRISPR could edit genes in human cells, confirming its translational potential. Parallel advances in understanding DNA repair pathways—such as non-homologous end joining and homology-directed repair—enabled scientists to harness CRISPR-induced breaks for either gene disruption or precise sequence correction.

By the late 2010s, CRISPR research shifted toward improving specificity, delivery, and safety. Engineered Cas variants, optimized guide RNA design, and advanced delivery system significantly reduced off-target effects. These advances moved CRISPR from laboratory research

into clinically viable applications, paving the way for human trials and regulatory-approved therapies.

Clinical Applications and Real-World Impact of CRISPR Gene Editing

CRISPR gene editing is now transitioning from experimental science to clinical reality, with early examples of CRISPR gene editing therapy entering regulated clinical practice:

- Blood Disorders: In December 2023, the U.S. FDA approved Casgevy (exagamglogene autotemcel), the first CRISPR-based therapy for sickle cell disease. This milestone followed earlier landmark clinical experiences, including the treatment of patients such as Victoria Gray where ex vivo CRISPR editing of hematopoietic stem cells restored fetal hemoglobin production and reduced disease complications. Regulatory progress in this area builds on earlier advances described in FDA approval of CRISPR-based treatment for sickle cell disease.

- Inherited Retinal Disorders: Early‑phase clinical trials using in vivo CRISPR delivery for Leber congenital amaurosis have reported improvements in visual function without serious safety concerns, highlighting the feasibility of direct tissue editing.

- Cardiovascular Disease: Adenine base‑editing therapies targeting PCSK9 have shown substantial and sustained reductions in LDL cholesterol in early human studies, suggesting potential for one‑time, long‑lasting cardiometabolic interventions.

- Cancer, Autoimmune Disease, and Diagnostics: CRISPR-engineered immune cells, including early iterations of CRISPR-modified T-cells and CAR-T approaches, are being evaluated for refractory cancers and autoimmune disorders. In parallel, CRISPR-based diagnostics are enabling rapid and highly sensitive disease detection of infectious and genetic diseases.

How Far Has CRISPR Technology Come Since 2012?

Since its introduction as a laboratory tool, CRISPR gene editing has advanced at an exceptional pace, mirroring broader progress across molecular medicine and fields such as clinical neuropharmacology:

- Transition from preclinical research to human clinical trials within a decade

- Achievement of regulatory approval for CRISPR‑based therapeutics

- Development of optimized delivery systems and engineered enzymes that enhance specificity and minimize unintended edits

This rapid evolution underscores CRISPR’s shift from theoretical promise to validated clinical modality.

What’s the Future of CRISPR Gene Editing?

Future development of CRISPR gene editing will focus on refinement, safety, and scalability rather than fundamental reinvention. Key directions include:

- Epigenome editing, enabling modulation of gene expression without altering DNA sequences

- Improved delivery platforms, such as lipid nanoparticles and optimized viral vectors, to achieve tissue‑specific targeting

- Artificial intelligence‑assisted guide RNA design, improving efficiency and reducing off‑target risk

Together, these advances aim to extend CRISPR’s applicability to complex, multifactorial diseases while improving accessibility.

Ethical and Regulatory Considerations

Despite its clinical promise, CRISPR gene editing raises important ethical and regulatory questions. Somatic cell editing, which affects only treated individuals, is broadly accepted under regulatory oversight. In contrast, germline editing, which introduces heritable genetic changes, remains prohibited or tightly restricted in most countries. Ongoing concerns include long‑term safety, equitable access, informed consent, and the potential for misuse, underscoring the need for robust governance and international collaboration.

Conclusion

CRISPR gene editing represents a defining advance in precision medicine, offering the ability to address disease-causing mutations at their biological source. Its clinical trajectory parallels other genome-based interventions explored for rare disorders, such as Hurler syndrome gene therapy. While long-term outcomes and accessibility challenges remain under evaluation, early clinical evidence confirms CRISPR gene editing as a transformative tool in modern medicine.

Understanding how clinicians, researchers, and patients interpret and adopt emerging genomic technologies is critical to responsible innovation. Platforms like MDForLives help capture these real-world perspectives to inform evidence-based progress.

Contribute to evidence‑based medical innovation. Participate in ongoing healthcare surveys and access insights from clinicians and researchers shaping the future of genomic medicine.

Frequently Asked Questions

What genetic diseases can CRISPR gene editing treat?

CRISPR gene editing is being used or studied for conditions such as sickle cell disease, beta‑thalassemia, inherited retinal disorders, rare metabolic diseases, and select immunodeficiencies. Some CRISPR‑based therapies have already received regulatory approval, while others remain in clinical development.

Which countries have restricted or banned CRISPR gene editing in humans?

Most countries prohibit germline CRISPR gene editing that results in heritable genetic changes. Somatic gene editing for research and therapeutic use is permitted under strict regulatory oversight in countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom.

Has anyone been cured using CRISPR gene editing?

Patients treated with FDA‑approved CRISPR‑based therapies for sickle cell disease have demonstrated sustained clinical benefits that are widely regarded as a functional cure, although long‑term follow‑up is ongoing.

What are the limitations of CRISPR gene editing?

Limitations include challenges with targeted delivery, potential off‑target edits, immune responses, cost, and scalability. Advances such as base editing and prime editing are designed to mitigate many of these constraints.

Is CRISPR gene editing legal in the United States?

Yes. CRISPR gene editing for somatic cells is legal in the United States and regulated by the FDA. Germline gene editing is subject to significant ethical, regulatory, and federal funding restrictions.

MDForLives is a global healthcare intelligence platform where real-world perspectives are transformed into validated insights. We bring together diverse healthcare experiences to discover, share, and shape the future of healthcare through data-backed understanding.