Many professionals in the Western world are reassessing the way they work. According to an August 2021 poll in the USA, 55% of workers plan to look for a new job in the coming year. (Source: Bankrate job seeker survey, July 28-30, 2021), while 56% of respondents said adjustable working hours and remote work were a priority.

While some people have left the workforce entirely, job security and better pay are also top concerns for employees. The graph below shows the number of resignations in all professions (source: Bureau of Labor statistics)

Working mums have faced a considerable added burden, facing childcare duties, virtual schooling (due to the COVID-19 pandemic), and their careers.

People have taken a step-back, to spend more times with loved-ones, or doing more rewarding things than long hours and ‘clocking-in’. the value of what we are doing at work is being questioned, and a number or people have made the decision, I need to make a change.

What about the Medical Profession?

It is no surprise nurses are quitting in droves, long shifts, poor wages, a system that does not appreciate them. A royal college of nursing survey from 2022, noted 63% of nurses said they were unable to take their full amount of annual leave due to pressure from their hospital to work overtime and locum shifts. A further 68% said they felt under “too much pressure at work”. The nursing and midwifery council (NMC) revealed that between April and September 2021, a total of 13,945 people nurses left, compared to 11,020 in the same period in 2020. The lack of investment in nursing education and training, as well as the lack of time for nurses to train and upskill, means there is little value of working in healthcare, and those that stay have a true passion for caring for others.

Why are Medical Doctors Quitting the Profession ?

Why is this affecting doctors? They are generally well paid, often get to choose their hours and sometimes moonlight in public and private clinics. In the UK, the GMC estimates around 4% (which equated to approximately 4,950 doctors) permanently leave the NHS every year. The European average is 3.2%. Over the last year, however that has risen, to 5.3%. Below we break down a few reasons why this

- The coronavirus pandemic.

During the last troubled year, thousands of exhausted doctors in the UK told the British Medical Association, they were seriously considering leaving the NHS by 2023, as many continue to battle stress and burnout without adequate respite from the exhaustion caused by the demands of the pandemic. At the beginning of the crisis, there was a lot of uncertainty regarding the virus. Doctors were doing their best on incomplete information, were being pressurized to conduct long shifts and help out at Covid centers. Hospitals were full, wards were unsafe, masks were being worn all day without any respite; there was a lack of supply of PPE; medicines; maintenance, replacement, and servicing of equipment; and many people were dying, including fellow doctors and nurses. Doctors were being exposed to higher viral loads, leading to more illness, and the infrastructure was not there to protect them. The mental, emotional, and physical burden proved breaking points for many doctors, and physician burnout or resignation grew considerably. This of course led to understaffing, resulting in increased workloads for those picking up the slack.

In the USA, according to a recent article from Mayo clinic (seen below), 1 in 5 doctors said that they will leave their practice within 2 years, and about 1 in 3 and other healthcare professionals intend to reduce their workhours over the next 12 months. This was data across 20,000 respondents at more than 124 institutions.

Despite all of this, data is still immature to prove that more physicians are leaving healthcare in 2021-22 than in the past, but the evidence does point that way.

- The pressures of getting to say “I am now a doctor”.

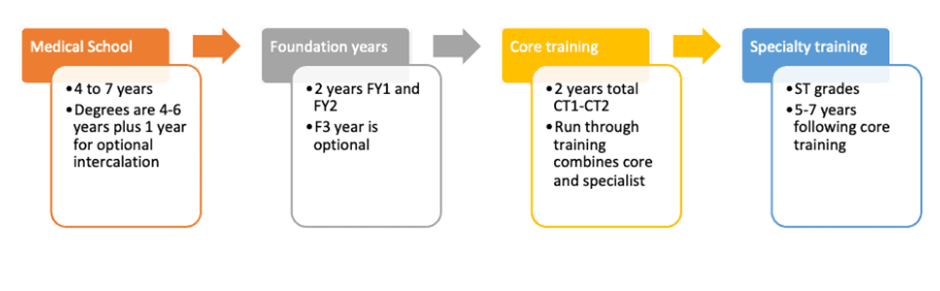

The fact is doctors have been leaving medicine for decades. One of the major reasons for this is the mental fortitude one needs to study for a career in medicine. In order to become a consultant, a person starts their training like all other Doctors at Medical School (4-7 years), this is followed by the Foundation years (2 years); then entering a training pathway either coupled – which includes core and specialty training (7 years total) as one run-through – or uncoupled, which has core training (2 years) and specialty training (5-8 years):

To study this many years without a break is tolling for any human (yes, even Doogie Howser. MD). A vast percentage of that residency involves placements in hospitals, and the workloads that entails. Medical students have to endure some of the most difficult examinations known to mankind, with competition fierce, unrelenting, and thankless at times.

Added to this, many doctors incur mountains of debt they need to repay when they are employed. Studying for that many years is not cheap, and it is hard to keep a second job to pay the bill when you are in competition with elite students. The average medical student graduates with over $200,000 in debt (some over $500,000)

The fact is, burnout between med students, residents and physicians is guaranteed at some point. Doctors have people’s lives in their hands, have possible lawsuits, botched operations, complications, adverse events, administration of the wrong medicines, lack of access to the latest machines/equipment/NGS panels/immunotherapy/targeted therapy. They have angry patients and staff and other doctors to deal with. They have endless multidisciplinary team meetings and value analysis committee meetings; the list of chagrins seems endless.

A study by the BMJ in 2017 noted the prevalence of physician distress, with recent national data suggesting that 44% of US physicians experience symptoms of burnout, characterized by emotional exhaustion and/or depersonalization, at least weekly:

“Care providers commonly develop intense interpersonal relationships with those they care for, often prioritising others’ needs over their own. While helping and caring for others can be extremely fulfilling, it can also drain your emotional reserves. Over time, this may result in burnout, which is indicated by feelings of overwhelming exhaustion, depersonalisation or cynicism towards people and work, and a sense of professional inefficacy” – Jane Lemaire, BMJ – Burnout among doctors July 2017

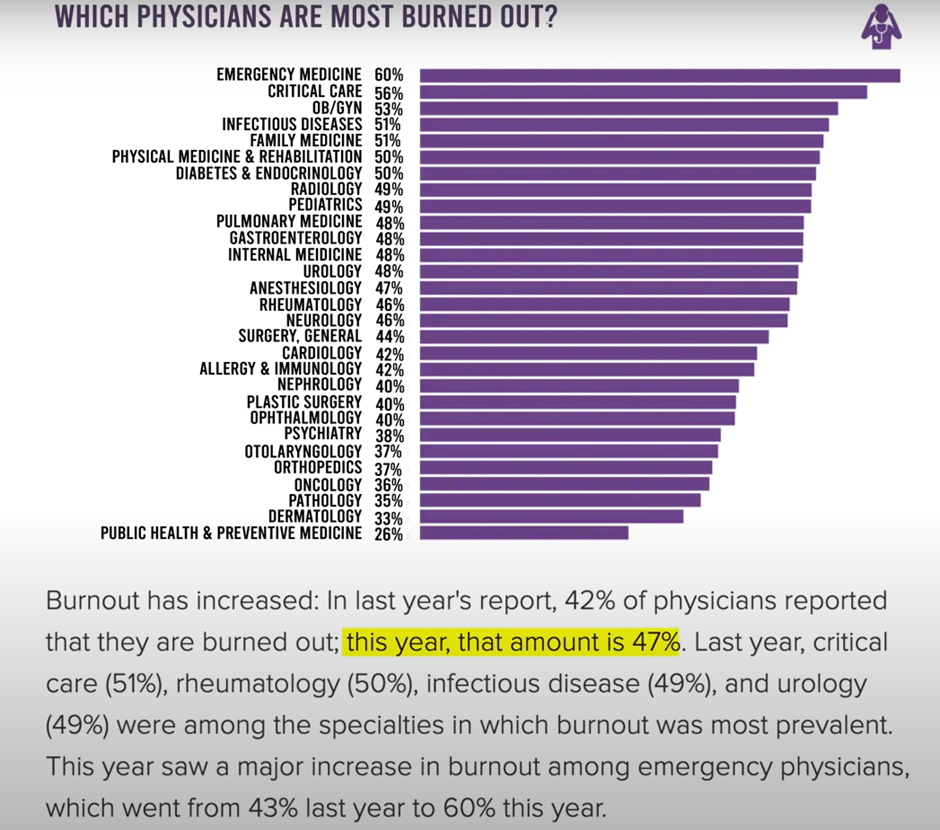

Below you can see an excerpt from an article by Medscape showing which physicians experience the most burnout, with critical care and emergency medicine unsurprisingly high in the list.

What Contributed Most to Burnout?

A few reasons sited by fellow doctors in the Medscape article included:

- Too many bureaucratic tasks (eg, charting, paperwork): 60%

- Lack of respect from administrator/employers or staff: 39%

- Too many hours at work: 32%

In short, doctors feel as if they are being exploited by the healthcare system, and feel if they voiced their complaints, they would not receive any sympathy from a wider public that have their own concerns and in general do not get paid as considerably. Without that release, the screw turns further.

- No incentive to stay

Whereas in other professions (particularly data sciences), employers offer enticing work packages (pension; comprehensive insurance including health, gym membership; work from home flexibility, utilizing the latest software monitoring tools etc.,), doctors do not feel valued, are given a generous wage, but are expected to work hard to justify that wage and are given no incentives to remain in their posts. In short, there is little value to be a doctor according to management. To key decision makers, the difference between having high performing doctors and low performing doctors is not as pronounced as in computer engineering, particularly when it comes to an end product and business success, this is why you never see hospital systems fighting and headhunting the best talent to come out of medical school. It is not as cool to be the next Edward Jenner as it is to be the next Elon Musk.

Conclusion

Nowadays, there is less stigma about doctors leaving. Social media has highlighted the reasoning and transparency into why doctors leave medicines, to give back their identity. Often these doctors have far more meaningful lives having left, have become entrepreneurs, start their own companies, become their own bosses, setting their own work times, choosing their own staff, setting their own algorithms and pathways to success. All in all, the first day after they quit, they have never been happier, and that is something that healthcare management need to be aware of.

Also read about

Drug Development through Surveys

MDForLives is a global healthcare intelligence platform where real-world perspectives are transformed into validated insights. We bring together diverse healthcare experiences to discover, share, and shape the future of healthcare through data-backed understanding.