Fear is one of the most deeply conserved emotional responses in human biology. From an evolutionary standpoint, it has enabled survival by prioritizing threat detection and rapid response. From a clinical and psychological perspective, however, fear occupies a more complex role. It can sharpen memory, alter perception, shape behavior, and, in some cases, persist long after the original threat has passed.

Understanding the science of fear requires moving beyond simplistic definitions. Fear is not merely an emotional reaction. It is a coordinated biological and psychological process involving neural circuits, neurotransmitters, contextual learning, and conscious interpretation. This article examines the biology and psychology of fear, why fear memories are especially durable, and how emerging neuroscience is shaping the understanding of fear-related disorders and treatment.

Science of Fear – Historical and Current Debates

Historically, fear was framed primarily as a reflexive response to danger. Early physiological models emphasized autonomic activation, identifying fear with sympathetic arousal and the “fight-or-flight” response. While this framework captured important elements of fear, it did not explain why fear can be learned, generalized, or persist in the absence of ongoing threat.

Contemporary neuroscience has reframed fear as a dynamic brain state shaped by learning, prediction, and memory. Rather than a single reaction, fear reflects the interaction between sensory input, emotional salience, contextual interpretation, and prior experience. This shift has important implications for understanding anxiety disorders, trauma-related conditions, and maladaptive fear responses.

Types of Fear

Fear is not a uniform experience. Different forms of fear are associated with distinct triggers, durations, and behavioral outputs.

Acute fear is typically phasic and stimulus-driven, emerging rapidly in response to an immediate threat. Anxiety, by contrast, is more tonic and anticipatory, linked to uncertainty and future-oriented prediction. Learned fear develops through conditioning, while social and existential fears emerge through higher-order cognitive processes.

Clinically, distinguishing between these forms matters. The mechanisms that sustain conditioned fear differ from those involved in generalized anxiety, and treatment strategies must account for these differences.

Science of Fear – Biology & Psychology

Fear arises from the integration of biological signaling and psychological interpretation. It is neither purely physiological nor purely cognitive.

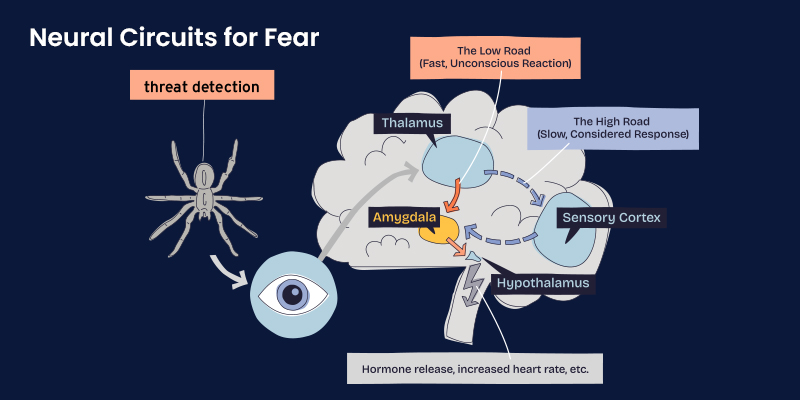

Neural Circuits for Fear

Fear processing relies on a distributed neural network. Sensory information is rapidly evaluated for emotional salience, with parallel pathways allowing both fast, automatic responses and slower, context-dependent appraisal. This dual-pathway system explains how fear can arise before conscious awareness and yet later be reassessed or inhibited.

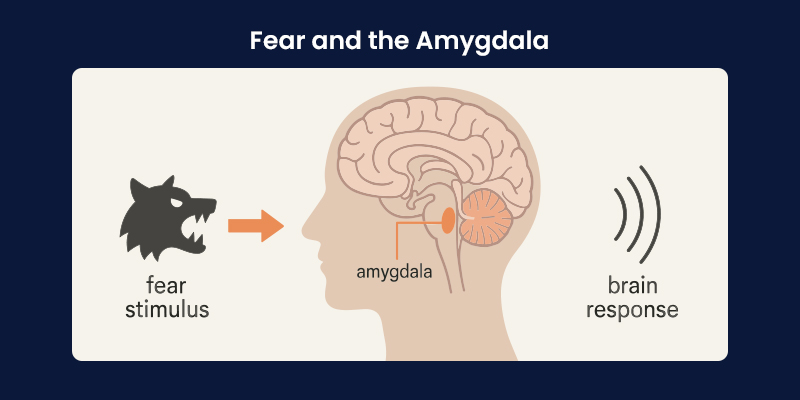

Fear and the Amygdala

The amygdala plays a central role in detecting emotionally salient stimuli and coordinating fear responses. Within the amygdala, the basolateral complex is particularly important for fear learning and memory. It integrates sensory input with neuromodulatory signals that influence how strongly a threat is encoded.

Research has shown that stress-related neurotransmitters, including norepinephrine, enhance fear memory by altering inhibitory and excitatory balance within amygdala circuits. This mechanism helps explain why emotionally intense or threatening events are remembered more vividly and persistently than neutral experiences.

Is Fear Adaptive?

Fear is fundamentally adaptive. It prioritizes survival by focusing attention, mobilizing energy, and reinforcing learning. However, adaptiveness depends on proportionality and context. When fear responses are excessive, generalized, or chronically activated, they can impair functioning rather than protect it.

From a clinical perspective, fear becomes problematic not because it exists, but because it becomes decoupled from present-day threat.

The Modulation of Fear

Fear expression is not fixed. Prefrontal and hippocampal regions modulate amygdala activity by providing contextual information and executive control. This top-down regulation allows individuals to distinguish between real and symbolic threats, such as differentiating a dangerous situation from a remembered or imagined one.

Disruption in these regulatory circuits has been implicated in trauma-related disorders, where fear responses persist despite cognitive awareness of safety.

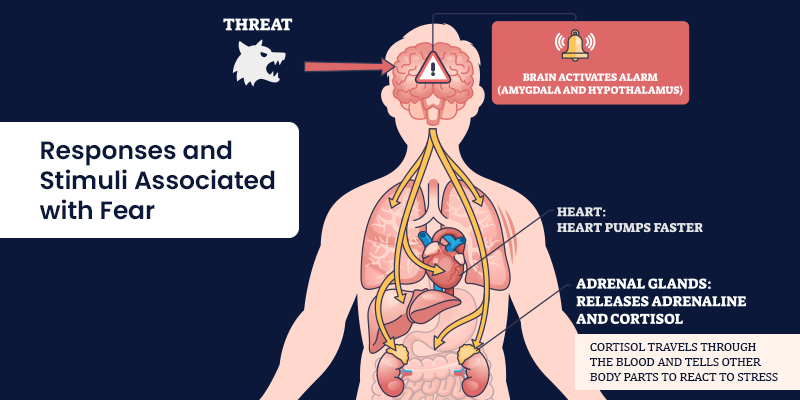

Responses and Stimuli Associated

Fear responses vary depending on stimulus characteristics and context.

-

Distance and Intensity

Proximity and intensity of a threat influence the type of response elicited. Immediate threats trigger reflexive defensive behaviors, while distant or ambiguous threats promote vigilance and anticipatory anxiety.

-

Other Stimulus Attributes

Predictability, controllability, and prior exposure also shape fear responses. Unpredictable threats tend to produce stronger and more persistent fear, whereas controllable threats are associated with reduced long-term impact.

-

Conscious Experience of Fear

Conscious fear reflects the subjective experience arising from underlying neural processes. While physiological arousal may be similar across individuals, interpretation and meaning vary widely. This explains why identical stimuli can evoke fear in one person and neutrality in another.

Three Recommendations for the Study of Fear

First, fear should be studied as a system rather than a single response. Integrating neural, psychological, and behavioral levels provides a more accurate understanding.

Second, context must be central to fear research. Memory, environment, and expectation profoundly shape fear expression.

Third, translational relevance should guide investigation. Insights into fear mechanisms are most valuable when they inform prevention, intervention, and treatment strategies.

Neuroscience of Fear in Treatment

Advances in the neuroscience of fear have reshaped therapeutic approaches. Exposure-based therapies, cognitive restructuring, and emerging neuromodulatory techniques all draw on an improved understanding of fear learning and extinction.

Persistent fear memories, such as those seen in post-traumatic stress, are increasingly understood as failures of inhibitory regulation rather than mere overactivation of fear circuits. This perspective shifts treatment goals from suppressing fear to restoring adaptive modulation. Real-world clinical insight plays a critical role in translating laboratory findings into practice. Platforms such as MDForLives contribute by capturing clinician and patient-reported experiences that reflect how fear is perceived, managed, and treated outside controlled research settings.

Interesting Facts About Fear

Fear memories are often encoded more strongly than neutral memories due to heightened neuromodulatory signaling.

- Physiological state, such as sleep deprivation or illness, can amplify fear perception.

- Fear can spread socially through observation and shared narratives, even wi

- Fear can spread socially through observation and shared narratives, even without direct exposure to threat.

- Repeated safe exposure can weaken fear responses through extinction learning, though original fear memories are rarely erased entirely.

Conclusion

Fear is neither inherently harmful nor universally beneficial. It is a biologically grounded response shaped by evolution, learning, and context. Its persistence in memory reflects adaptive mechanisms designed to prioritize survival, yet these same mechanisms can become maladaptive when fear outlives the threat that created it.

For clinicians and healthcare systems, understanding the science of fear is essential for addressing anxiety, trauma, and stress-related conditions effectively. Integrating biological insight with real-world patient experience allows for more nuanced, responsive care. MDForLives supports this integration by surfacing applied insights that illuminate how fear operates in everyday clinical and human contexts.

Support evidence-informed understanding of fear and mental health. By participating in research through MDForLives, healthcare professionals and patients contribute real-world insights that help translate neuroscience into effective care.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is fear learned?

Fear can be both innate and learned. While some fear responses are biologically predisposed, many are acquired through conditioning and experience.

Is fear healthy?

Fear is healthy when it is proportionate and contextually appropriate. It becomes problematic when it is excessive, persistent, or disconnected from real threat.

What are the benefits of fear?

Fear enhances survival by sharpening attention, reinforcing learning, and motivating protective behavior.

How to remove fear from the body?

Fear responses can be reduced through techniques that promote extinction learning, emotional regulation, and contextual reassessment rather than complete elimination of fear.

MDForLives is a global healthcare intelligence platform where real-world perspectives are transformed into validated insights. We bring together diverse healthcare experiences to discover, share, and shape the future of healthcare through data-backed understanding.