When the Danish footballer Christian Eriksen collapsed from a cardiac arrest on Saturday 12th June 2021, the world was in shock. He had no previous signs of heart disease. He was only 29 years old, was fit and healthy, was not suffering from COVID-19, and contrary to popular opinion, had not been ‘overplayed’ during the 2020-21 season (having missed the majority of Inter Milan’s season due to falling out of favor with Inter Milan boss Antonio Conte). Thankfully, he survived. Though he most probably will never play professional football again.

How this happened will come to light over the next few days or weeks. He is not the first sportsperson to have done so. Also in football, Marc Vivien-Foé, a 28-year-old Cameroonian, died of a heart attack on the pitch on 26th June 2003. Indeed, outside of professional sport, it is estimated about 2,000 young, seemingly healthy people under age 25 in the United States die each year of sudden cardiac arrest.

Why is this?

Probably the earliest medical advice I was given as a child was: If you want to keep your heart strong, a) eat your greens, and b) do regular exercise. Like most normal people, the rate I do both have varied throughout the years. I sometimes wish I had the discipline of an elite-level sportsperson. The £trillions pumped into top sport boggles the senses. Prize individuals have become precious investments, and teams of professionals are employed to ensure an athlete remains at their peak. The biggest sporting teams pay millions for dieticians, doctors, psychiatrists, etc., the science of sport has been painstakingly analyzed, scrutinized and improved upon. How then do athletes at the top of their game, who are monitored, screened and tested week in week out, suddenly suffer from life-threatening cardiac arrests?

Before Christian Eriksen joined Inter Milan on 28th January 2020, a medical team would have done a pre-participation screening. This consists of a structured history and physical examination, which includes an ECG and echocardiogram to identify any risks of SCD (sudden cardiac death) or CAD (coronary artery disease). If Eriksen was listed high or even medium-risk, he would not have been signed. Such is the strict criteria for purchasing a £16.2M player whose wage was £12.6M per year.

When a sportsman, who has had no prior signs, suffers a heart attack while in physical activity, it suggests underlying silent or unknown coronary, myocardial or valvular heart disease, and channelopathies. The exercise may have triggered the development of malignant arrhythmias.

In Eriksen’s case, it was immediate and life-threatening arrhythmia (an irregular heartbeat pattern – the heart is unable to pump enough blood into the body, causing a collapse).

Thanks to the quick thinking of the officials that Eriksen made it out of that stadium alive. From the referee Anthony Taylor (whose response time from the moment Eriksen fell, to beckoning the medical team onto the pitch was 6 seconds), to the players (especially Danish captain Simon Kjaer, who immediately scrambled to clear Eriksen’s airways), the team doctors and the emergency services (who within minutes were performing CPR before resuscitating him using an AED – automated external defibrillator). The FDA states that the probability of survival “decreases by 7% to 10% for every minute that a victim stays in a life-threatening arrhythmia”, so all those people at the front line can rightly be called heroes.

It also shows you the importance of immediate CPR and AED (panels attached to the AED assess a patient’s heart rhythm and calculate whether it is needed. If an arrhythmia is detected, the AED will recommend an electric shock to re-stimulate the heartbeat to a regular pace, which may be needed more than once). If even one of these tangibles was not as rapid in response, Eriksen would have been another tragic statistic of sports-related SCD (sudden cardiac death).

It is perhaps unsurprising that the incidence of SCD is significantly lower in athletes than in the general population. The annual incidence of sports-related SCD is reportedly 4.6 per 1 million population, compared to 50-100 per million in the general population. This risk in the athlete is increased, based on age, race, ethnicity, gender, training level, and specific sport. SCD in sport, tends to happen in the middle-age group (>35yo). 80% of these deaths are due to atherosclerotic CAD. The risk of SCD or sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) is 5x greater when the athlete is training. The SCD incidence is higher in black sportspeople (1:21491 athlete-years), compared to white (1:68354 athlete years).

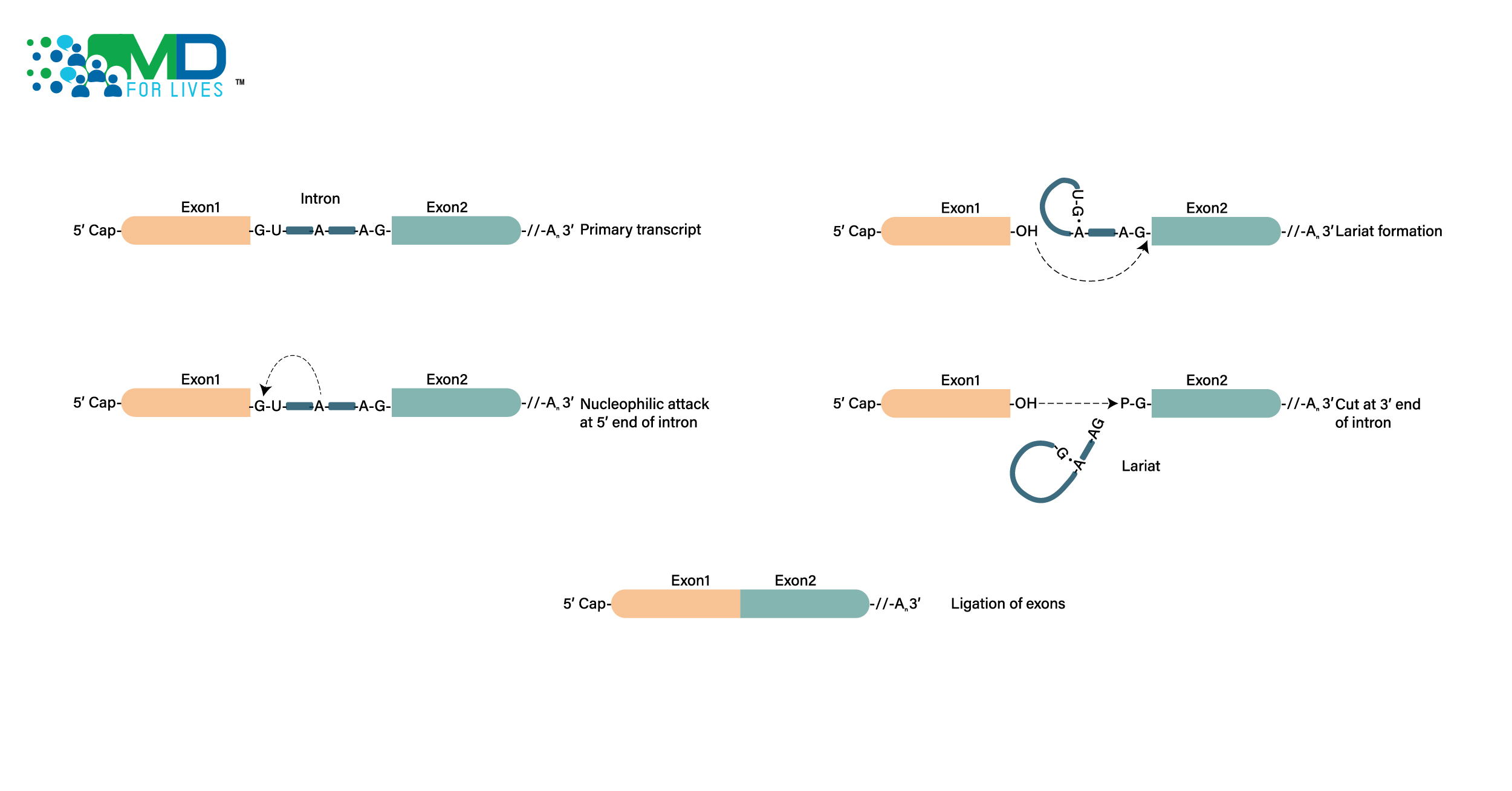

The most frequent cardiac causes of SCD in younger athletes (<35yo) are:

SADS (sudden arrhythmic death syndrome) 56%,

HCM (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) 36-48%,

Congenital anomalous coronary artery origin from opposite sinus 14-17%,

ARVC (arrhythmic right ventricular cardiomyopathy) 4-11%,

Myocarditis 6-7%,

Ion channelopathies 4%,

Atherosclerotic CAD 2-3%.

The table below outlines the causes of SCD in all types/subtypes with pathology.

Causes of SCD in sport

In older sportspeople (>35yo), most SCD’s were due to CAD incidences (acute thrombotic occlusion, fixed coronary stenosis without thrombosis, and acute plaque rupture).

With moderate to high-intensity exercise, performed at regular intervals over a long period of time, the subsequent positive pleiotropic effect helps to reduce the overall risk of atherosclerosis and acute coronary syndrome sevenfold. An active sportsman will have a 50 times lower risk of myocardial infarction during exercise than when at rest, which is known as the sporting paradox.

Early and consistent screening

There is a need for more vigorous and stricter screening protocols/guidelines in evaluating sportspeople.

It should start from a young age. If an athlete is showing signs of a future in the sport, the lead physician (preferably cardiologist) should conduct an extensive physical examination, including careful auscultation (several positions and maneuvers), to detect any heart murmur/dynamic murmur due to left ventricular outflow tract obstruction.

If an athlete has a family history of SCD or cardiomyopathy, they should have mandatory ECG and an evaluation of their echocardiographic baseline and intervals. The ideal would be further imaging and electrophysiological testing.

There should be a 12-lead ECG screening to detect for specificities like WPW syndrome, HCM and ARVC, and ion channelopathies (e.g., Brugada syndrome, Long QT syndrome). Though, it is important to understand the limits of ECG, as some natural physiological changes in the readings can lead to misdiagnosis.

An exercise ECG is also important in identifying silent CAD in older athletes.

Pre-participation screening in young, competitive athletes.

Steps in pre-participation screening for older athletes

How to utilize the ECG report

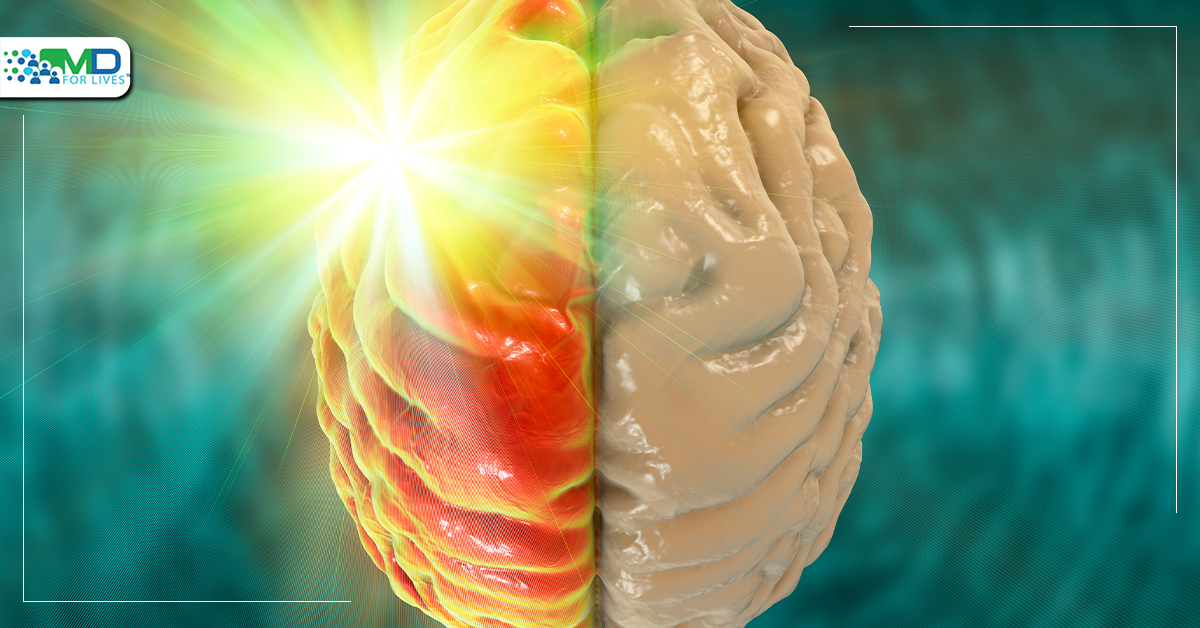

It is important to utilize ECG, imaging data, and objective functional capacity in differentiating the physiological adaptions of ‘athlete’s heart’ (electrical/structural/functional) with the pathological changes (HCM, ARVC, IDCM). MRI screening is important to look for possible signs of apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy:

Or apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with infarction:

The MRI below with gadolinium contrast shows diffused hyper-enhancement/uptake in LV/RV/ATRIAL WALLS, diagnosed as amyloidosis:

Much like the Greek gods valued the prowess of Hercules, and the Romans gloried at their gladiators, we rightly adore our sporting heroes. They are a reverential symbol of the summits of human capabilities, but we need to stop taking their health for granted. If we have to push them to the brink of human endeavor, at least give them a fighting chance. A reduction in long bouts of intensity would be ideal, but the powers that be, the sponsors and billionaire sporting owners will not allow it. Thus, constant and consistent checks of our sportspeople, utilizing physical examination, ECG, MRI, and all other assessments for coronary heart risk factors, at as young an age as possible, and then throughout their sporting lives, only then can we say that we did our best in prolonging an athlete’s life as much as possible.