Our gut microbiome does far more than just aid digestion — it plays a vital role in generating essential vitamins, protecting us from infections, and regulating our immune system. Two recent clinical trials highlight the gut microbiome’s centrality in human health from the very beginning of our lives. In today’s world, where early nutrition and preventive care are gaining new importance, understanding how gut bacteria influence our health from birth can help us make smarter choices for lifelong wellness.”

Clinical Trials Highlight the Importance of Gut Microbiome in Human Health

Clinical Trial 1 – A potential probiotic treatment for premature babies

A research team mainly located in Calgary, Canada tested a probiotic treatment for very premature infants. Babies born before 32 weeks of gestation are vulnerable to necrotizing enterocolitis and neonatal sepsis, which are frequently fatal. Formula-fed babies are at greater risk. There is growing evidence that probiotics – combinations of beneficial microbes—can help prevent these conditions.

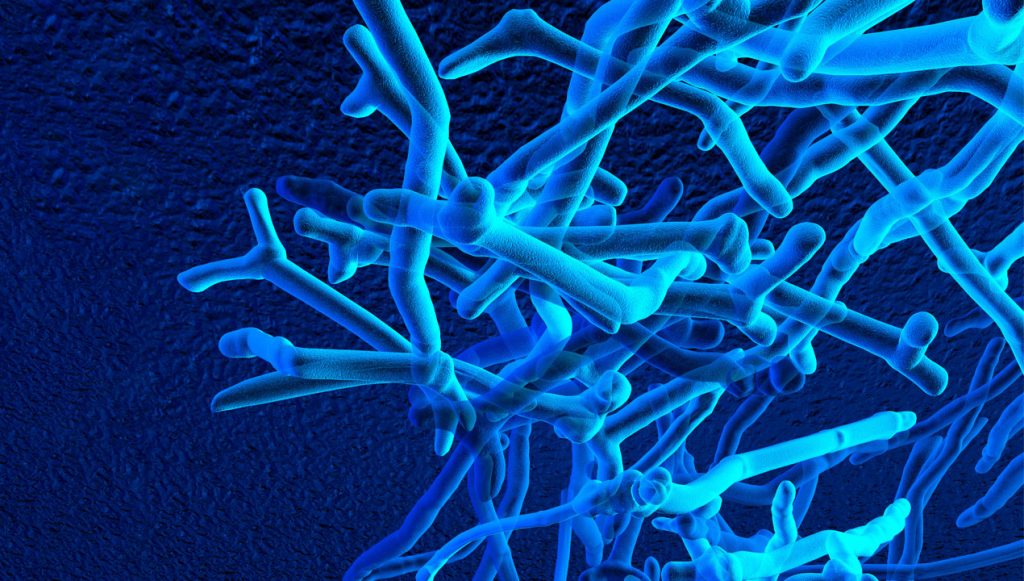

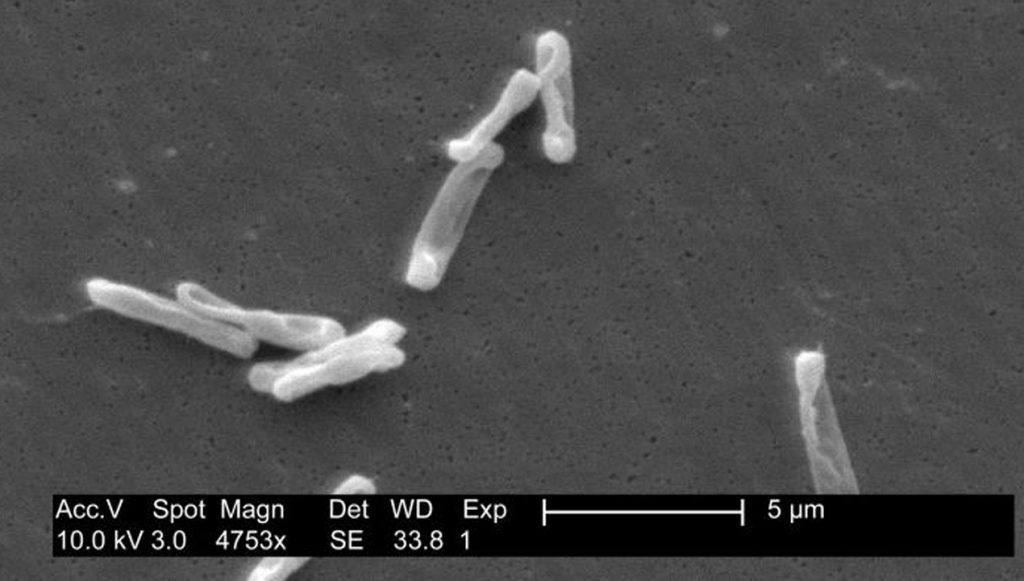

The Canadian team formulated a probiotic treatment consisting of four Bifidobacterium strains (In neonates, Bifidobacteria are some of the most abundant members of the microbiota in the gut), plus one Lacticaseibacillus strain. This probiotic was administered daily to very premature infants.

The researchers found that the treatment helped the preemies’ gut microbiomes mature and stabilize faster and provided benefits for the infants’ gut immune health. The treated babies’ microbiomes were also more diverse. The authors call the anaerobic Bifidobacterium “ecosystem engineers,” a term referring to a species that modifies its own environment and changes the opportunities and resources available for other species.

Other recent research suggests that some of the components of human breastmilk serve as food for babies’ beneficial gut microbes, including Bifidobacterium and others. Moreover, breastmilk is itself a source of microbes, and these microbes seem to contribute to breastfed babies’ developing microbiota in the gut.

Clinical Trial 2 – Microbial therapies for dysbiosis in the gut

Microbiome-based therapies are increasingly being studied for treating dysbiosis in the gut. Dysbiosis refers to disruptions to the microbial balance in the body, often along with lower microbial diversity and increased susceptibility to pathogenic microbes. Dysbiosis can be the result of premature birth and can occur in adults after antibiotic use, with inflammatory bowel disease, and with many other conditions

Engraftment, or stable establishment, of therapeutically applied microbes in a human host can be a challenge, as adult microbiomes seem to resist colonization. To remedy this, scientists have tried antibiotic pretreatment in advance of microbiota transplantation (such as fecal transplant), but antibiotics have their own negative effects on the microbiota.

Clinical Trial 3 – Breastmilk derivatives to feed gut microbes

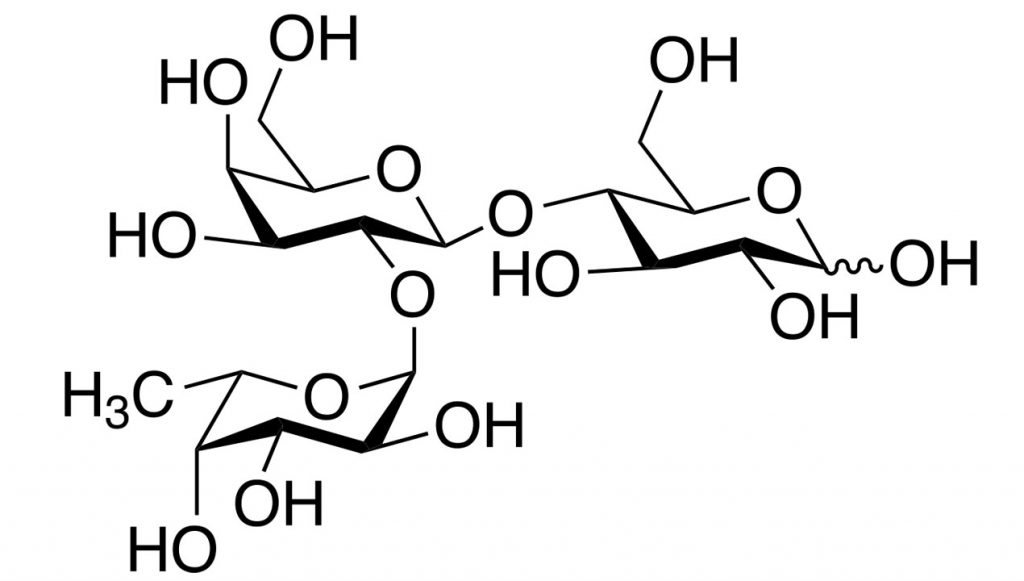

In a study reported in Cell Host & Microbe in May 2022, a research team took a different approach. They used specific, complex sugars found in human breastmilk (human milk oligosaccharides) to aid the beneficial microbe Bifidobacterium infantis in establishing itself in adults’ intestines. The team formulated a synbiotic – a combination of one or more microbes along with a food that supports those microbes – consisting of Bifidobacterium infantis and a mixture of human milk oligosaccharides.

Human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) are the third most abundant solid component in human breastmilk. These structurally diverse molecules are found in no other species. HMOs feed members of the microbiota in the guts of infants and help favor the growth of certain species over others. They also bind to receptors on immune and epithelial cells and appear to help shape immunity in the infant gut.

The authors of the recent study found that around half of the adults given a daily oral dose of the synbiotic for 7 days, followed by the HMO mixture through day 14, showed signs that the B. infantis bacteria were replicating in their guts (engraftment); however, once HMO dosing stopped, the level of bacteria gradually declined to below the limit of detection. Meanwhile, adults dosed with the B. infantis component without HMOs for the first 7 days had very little B. infantis in their stool by day 14.

In a separate experiment, the research team found that their synbiotic could help B. infantis engraft in mice whose microbiota had been altered to resemble either the human infant microbiota or that of people with dysbiosis.

Microbiome Health – What are the implications of this?

The above findings could potentially help improve the success of probiotic therapies and microbiota transplants for infants and adults. There is current research on the addition of specific HMOs to infant formulas, as well as early-stage research on the therapeutic potential of HMOs for allergies and other conditions in adults. The authors of the second study suggest that synbiotics could have therapeutic potential for various diseases that involve dysbiosis in the gut.

Also read

MDForLives is a global healthcare intelligence platform where real-world perspectives are transformed into validated insights. We bring together diverse healthcare experiences to discover, share, and shape the future of healthcare through data-backed understanding.