When it comes to lung cancer, the patient and the physician often feel like Danny in The Shining, navigating through the Overlook Hotel’s unicursal labyrinth, survival lies left or right, Jack Torrance giving chase from behind. Lung cancer is the most common cancer in the world. More people die each year from lung cancer than from breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers combined. You can only imagine the difficulties faced by oncologists, pulmonologists, thoracic surgeons, radiologists 30 years ago when treatment paradigms for many subsets were as grave as patient prognosis. In this blog, we explore the landscape of lung cancer research, tracing key discoveries from the past, examining current diagnostic and treatment strategies, and highlighting emerging innovations that could shape the future of patient care.

We are fortunate to be in an era of state-of-the-art tools for early detection of lung cancer, in imaging (CT, 3D PET/CT), biopsy (bronchoscopy, lung needle biopsy, EBUS, EUS, neck lymph node biopsy), or biomarkers, such as PDL1, EGFR, ALK, BRAF, VEGF, KRAS, RET, MET, ERBB2 (HER2), TMB, ROS1. Upon a positive result, we have mediastinoscopy, thoracoscopy, advanced MRI, and ultrasound scanners for further diagnosis. We have multi-disciplinary teams (MDT), CCGs, value analysis committees (VAC), the best in practising, experienced physicians; NICE, the FDA and EMA giving us expert advice, meticulous data assessment, up-to-date analysis on a barrage of ever-evolving guidelines. We have early access and reimbursement and big-pharma, bringing products quickly and effectively through several clinical trial stages, introducing ground-breaking targeted therapies and immunotherapies, like pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor), erlotinib (targeting EGFR tyrosine kinase), capmatinib (targeting Met Exon-14), bevacizumab (targeting VEGF), sotorasib (targeting KRAS G12C), lorlatinib (targeting ALK), etc.

How has this Advancement Changed the Landscape of Lung Cancer?

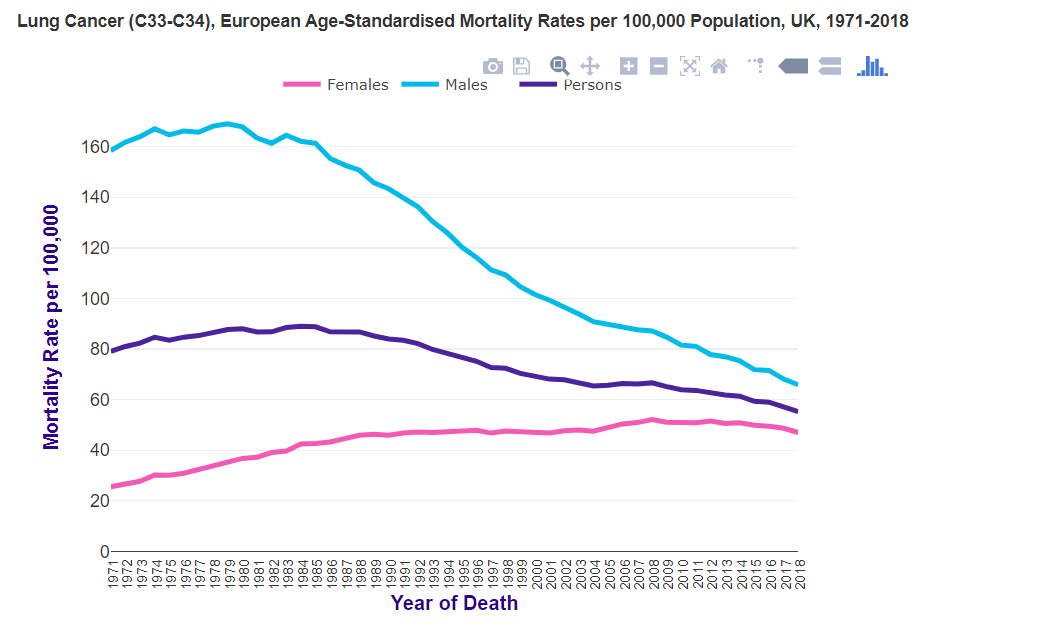

In the UK, lung cancer death per 100,000 population has reduced by 29% from 1971-2018.

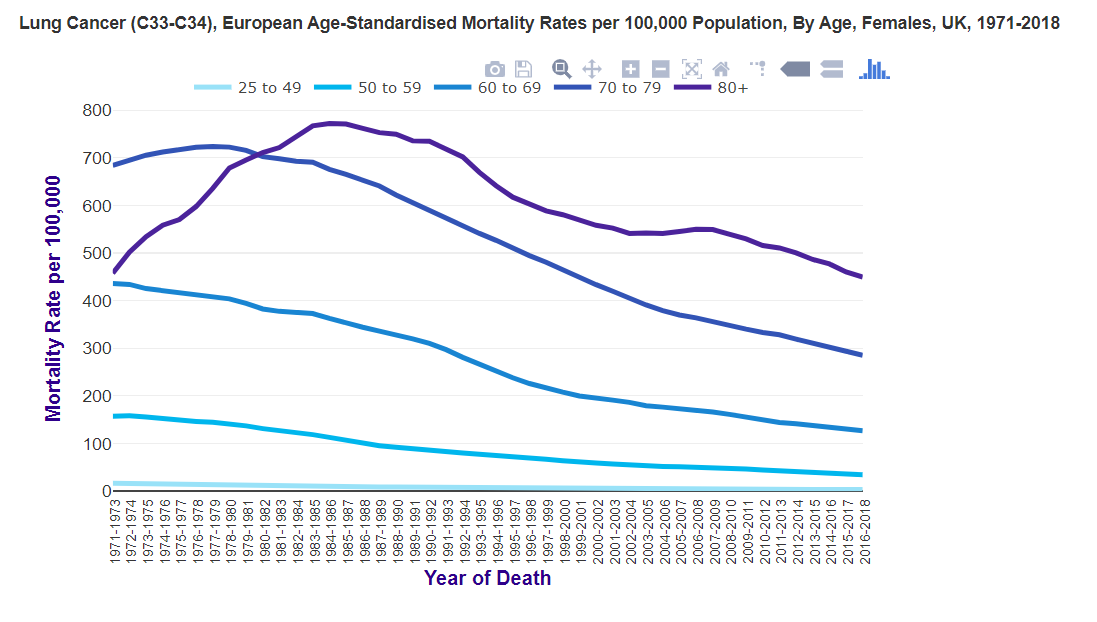

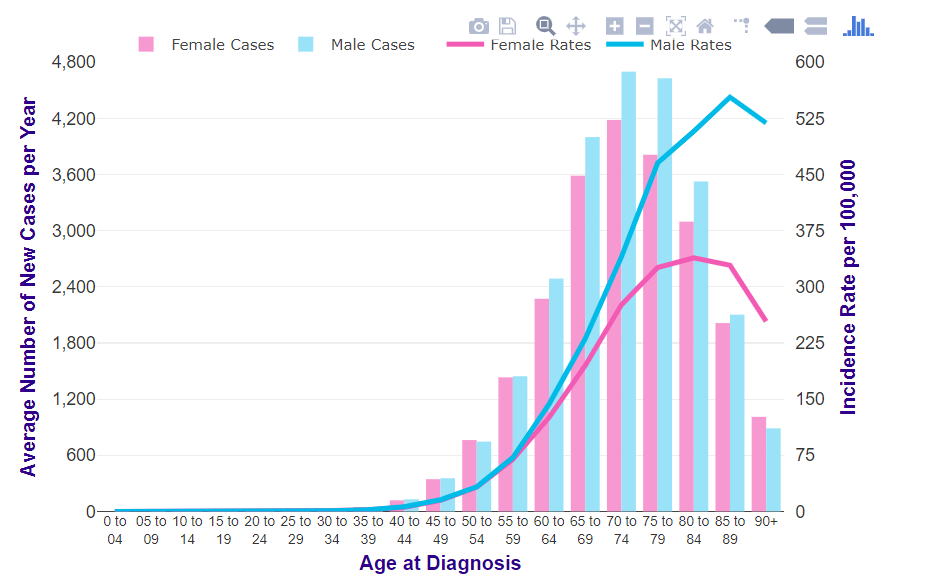

Though prevalence amongst younger generations is down considerably and the options for this new generation are bountiful, what about the “problem elderly population”? As you can see from the graph below, the incidence in the 80+ age group remains consistently dour.

Indeed, data from cancer research shows the incidence of new cases of lung cancer amongst the 80+ generation (particularly males) has risen (see graph below):

Lung cancer (C33-C34), Average Number of New Cases per Year and Age-Specific Incidence Rates per 100,000 Population, UK, 2015-2017

The reasons for this may be obvious: older generations tended to start young, lured by the “Laramie-peak” years (1930-1950), James Dean and Humphrey Bogart, Audrey Hepburn and Marlene Dietrich. Smoking was cool. It was a trend that continued to grow for the next 50 years, despite protestations from the vast majority of medical professionals. Sir Richard Doll and Austin Hill’s landmark article, published in 1950 in the British Medical Journal, which confirmed suspicions that lung cancer was associated with cigarette smoking, the 1962 Royal College of Physicians report on “Smoking and Health”, the 1965 US ban on cigarette advertising on TV, the UK Health Education Council in 1969, The World Health Organisation in 1970, The ASH report ‘Action on Smoking and Health’ in 1971, Independent Scientific Committee on Smoking and Health (ISCSH) in 1973, etc.

Lung Cancer Treatment – Advancement Research History

As the 1970s and 1980s drew to their close, it was hoped that increasing regulation, taxation, and public awareness campaigns would help curb cancer rates. Not so, cigarettes were still being passed under the table, encouraged by big business, supported by governments throughout the world. As in gambling, it was more harmful to the economy not to have them in circulation and the healthcare professional bore the brunt. By 1990, the general treatment pathway for an NSCLC patient was surgery. Radiotherapy was used postoperatively, to palliate brain metastases and spinal cord compression, helping improve quality of life.

Research on Role of Chemotherapy

The role of chemotherapy in 1990 was controversial. Globally, many physicians did not support a regimen of chemo, especially in those patients with tumor shrinkage, due to doubts on overall survival, lack of curative potential and treatment-related toxicities. The early 2000s were a watershed period in lung cancer. In 2003, the Tobacco Regulation Act regulated smoking in public places, tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship. At the same time, The National Lung Screening Trial (a multicentre, randomized controlled trial), compared low-dose helical CT with chest radiography in the screening of current and former heavy smokers for lung cancer (primary endpoint – lung cancer mortality). 53,456 participants, 55-74 years of age, with a history of cigarette smoking (>30 pack-years). By 2011, the results showed:

A positive screening rate of 24.2% with low-dose CT, compared to 6.9% with radiography, and a relative reduction in mortality from lung cancer with low-dose CT screening of 20.0%. The rate of death from any cause was reduced in the low-dose CT group, as compared with the radiography group, by 6.7%. It was clear, earlier screening was important. The European Union published the following 10 points related to implementing lung cancer screening in Europe:

| (I) The low-dose CT, the only evidence-based method for the early detection of lung cancer shown to provide a mortality reduction; (II) A validated risk stratification approach be used to select who should be screened; (III) The potential benefits and harms should be discussed and smoking cessation advice offered; (IV) Management of nodules should use volumetric measurements; (V) National quality assurance boards be set up by professional bodies; (VI) Management of nodules detected in different settings (prevalent screen, incident screen, clinical practice) should be managed with different protocols due to different pre-test lung cancer risk; (VII) A personalized approach to lung cancer screening be considered; (VIII) Management of lung nodules should be done by multidisciplinary teams with the aim of minimizing harm and ensuring patients receive the most appropriate treatment; and (IX) Planning for low-dose CT screening should be started throughout Europe because it has the potential to save lives. |

Overall treatment from 2000-2020 still favored surgery, though patients were encouraged to consider postoperative chemotherapy after curative resection, with a 5% survival advantage over resection alone. Radiotherapy was added to this, but physicians did so with care, using CT and 3D planning to define the limits of the tumor and to allow a safer, more focussed higher dose. Radiotherapy has been especially successful in palliating symptoms of lung cancer (cough, hemoptysis, bone pain, superior vena cava syndrome, and cerebral metastases).

Research on Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

PET was also added to the mix in 2000, working especially well in pre-treatment staging, as radical therapy relies on the tumor being confined to the irradiated site. In 2015-20, revolutionary immunotherapy agents entered the field, starting with nivolumab (approved 2015-2017), which targeted the programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) receptor, its main indication being for NSCLC patients with progression on or after platinum-based chemotherapy. Trial results from CheckMate 017, showed OS rates of 13.4% for nivolumab versus 2.6% docetaxel monotherapy, with a 5-year PFS rate of 8.0% versus 0%.

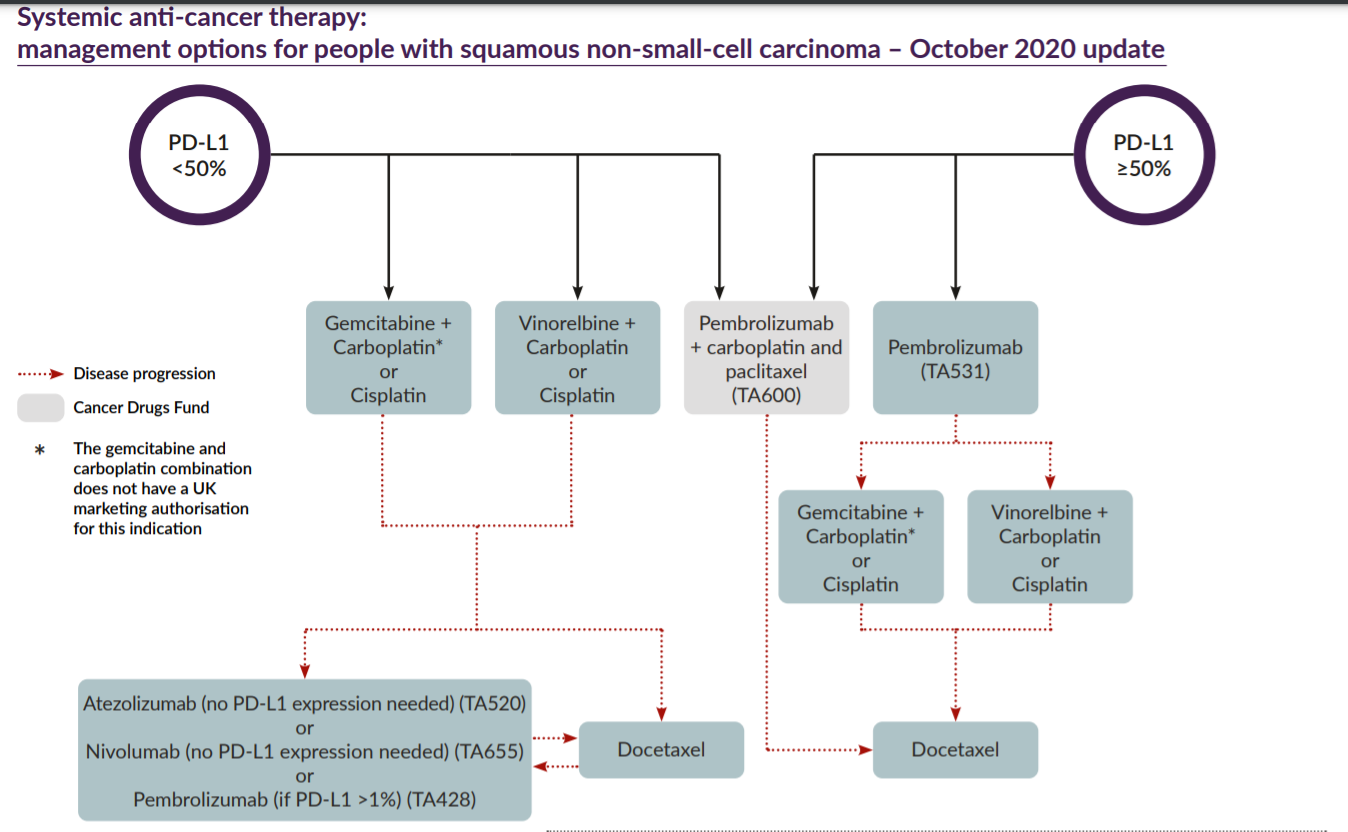

For patients unable to have surgery, 2 major players joined the party. In 2019, pembrolizumab was approved for the first-line treatment of patients with stage III NSCLC who were not candidates for surgical resection or definitive chemoradiation or mNSCLC. In 2020, atezolizumab was approved. A phase 3 trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed atezolizumab resulted in significantly longer overall survival compared with platinum-based chemotherapy among NSCLC patients with high PD-L1 expression, regardless of histologic type.

Research on Targeted Therapy

Targeted therapy also provided exciting new trial data. Gefitinib and erlotinib, targeting overexpression of EGFR mutations and its ligands, have demonstrated antitumor activity in patients with advanced NSCLC who have relapsed after treatment with conventional chemotherapy regimens, with a low toxicity profile.

There are currently no specific treatment recommendations for advanced NSCLC patients aged 80 years and older. With an aging population, there is a need for data that can assist the clinician in the management of 80y+ patients with advanced NSCLC. The outlook is poor no matter the treatment, with a median survival of 4 to 6 months. Chemotherapy, especially with newer drugs like carboplatin or cisplatin, plus vinorelbine, gemcitabine, or a taxane have shown good results, have easier administration on an outpatient basis; fewer side effects, such as nausea, vomiting, and hair loss; and an improvement in quality of life, which had perhaps been lost by the side effects of the chemotherapy itself.

Immunotherapy and targeted therapy are highly likely to be future first-line options and perhaps standard of care as patients and personalized biomarkers are being identified and addressed earlier. Until then, chemotherapy is an old friend, cozying up to us as he brings us our pipe and slippers.

A billboard outside a well-known cigarette manufacturer in 1984 brazenly proclaimed: Smoking is here to stay. It has been a connection for many people to the earth, a stress-reliever, a sign of belonging to the wild bunch, a habit through the centuries, but with the market saturated and expensive, younger generations moving onto e-cigarettes, or other habits, are we coming out of the Outlook Hotel’s winding maze, with Jack Torrance frozen somewhere behind? Let’s not look back, for he may re-thaw.

-Dr Amit Shah,

MDforLives Panellist, UK